Historic women who shaped the North Coast

Published 9:00 am Friday, March 22, 2024

- Celiast Coboway Smith operated a store and sawmill along the Lewis and Clark River and also ran a subscription school.

What was life like for women living on the North Coast centuries ago?

In pictures that wind up the sides of the Astoria Column are many men who have inhabited and shaped the Columbia-Pacific region — familiar names like Capt. Robert Gray and explorers of the Corps of Discovery.

Trending

But the stories of women who have made their homes here and impacted historic events, though often more difficult to reconstruct, are also essential pieces of the region’s heritage. Here are a few of their stories.

Celiast Coboway Smith

Growing up on the ancestral homeland of the Clatsop people, Celiast Coboway, later Celiast Smith, lived with her family in a cedar plank house, wore clothing made from cedar bark and learned myths and spiritual stories.

In 1805, the Corps of Discovery arrived. Chief Coboway, Smith’s father, visited Fort Clatsop and traded with the expedition members.

The next spring, the Corps departed in a stolen Clatsop canoe, and the fort and its furnishings were left to Chief Coboway, who used it for winter hunting. His daughter and her sisters played in the fort as children, hardly imagining how much the arrival of the explorers would change the way of life for their people.

In 1811, employees of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Co. arrived on the ship Tonquin and built Fort Astoria. In their teenage years, Smith and her sisters each married men stationed there. They resettled around Fort Vancouver and in the Willamette Valley, where they raised their children.

Smith remained close to her two sisters throughout her life. Her nephew attended school at Fort Vancouver, where he excelled at languages, including Clatsop, Tillamook, Kalapuya and Spokane.

Trending

Smith, who also used the Anglicized name Helen, married a baker. When she discovered her husband had another wife living in Canada, she left him for a schoolteacher at the fort named Solomon Smith.

Outbreaks of illnesses at Fort Vancouver caused the sisters to leave, and the couple decided to move to a farm. There, they opened a schoolhouse and later established a water-powered sawmill.

In 1840, they returned to the Oregon Coast, where the Clatsop people welcomed them home with a ceremony.

Being a white American, Solomon was eligible to receive a land claim, so the family settled near Seaside. He participated in the vote to form the Provisional Government of Oregon and later represented the North Coast in the Oregon legislature.

The years Celiast had been gone were devastating for the Clatsop people. They had suffered smallpox epidemics and seen a village burned.

Protected to some extent because of her marriage to a white man, Celiast continued to operate a store and sawmill with her husband along the Lewis and Clark River. She also ran a subscription school for a time. She died in 1891 and was buried with her husband in Warrenton.

Their son, Silas Bryant Smith, became a lawyer and the first Native member of the Oregon Historical Society. He conducted oral interviews with Clatsop elders that were essential to the preservation of sites within Lewis and Clark National Historical Park and fought for the preservation of local tribal heritage.

His descendants continue that legacy. One descendant, Charlotte Basch, now lives in Washington state and was instrumental in remaking a Fort Clatsop Visitor Center video to more accurately portray the Clatsop-Nehalem tribes’ story.

Basch portrayed her ancestor in the film and has also served as a model for a 60-foot-long mural in Seaside that depicts scenes of Native life.

Inez Eugenia Adams Parker

Born in 1845 in Illinois, Inez Eugenia Adams, later Parker, was a young child when her family crossed the plains by covered wagon. Her family settled in Oregon City, where her father began publishing the Oregon Argus.

By age 11, she began setting type for the paper, a laborious job that involved selecting each letter and arranging it backward and upside down in a type stick. Typesetting was a male-dominated industry, and as a child, she was among the first female typesetters.

As a child, Inez Parker began typesetting newsprint, and, with her husband, would later take over the publication of the Astoria Marine Gazette.

The newspaper had subscribers all over the country, and Abraham Lincoln enjoyed the Oregon Argus’ editorials long before he ran for office. The two began corresponding, and President Lincoln later appointed Parker’s father a position as a customs official in Astoria, where the family moved in 1861.

One of her father’s employees at the customs office was a man named Wilder Parker. The two courted and formed a marriage that allowed an unusual amount of autonomy for norms at the time.

Wilder Parker was a well-educated man from Vermont, who was an early participant in California’s gold rush before heading north with three of his brothers. He started a sawmill in Astoria and became deeply involved in civic affairs.

After their marriage, Inez and Wilder Parker partnered in several business ventures that listed both of their names on the deeds. They ran a sawmill in Astoria and built several buildings in town.

The couple also took over the publication of the Astoria Marine Gazette for two years, which notably argued in favor of Black suffrage in 1865.

As the town of Astoria grew, water access became a challenge. Early settlers had drawn water from many small creeks running down from the hills, but as the population increased, residents at the highest points had more access to clean water.

The idea of diverting springs into a water reservoir gained hold, and in 1876, Inez and Wilder helped design and finish the project. They helped to form the Astoria Water Works, which would later be sold to the city.

Honored as a pioneer in creating the Astoria water system, Wilder’s name can still be seen engraved in the stone building at the entrance of the water reservoir.

He served as postmaster, oversaw the building of a railroad between Astoria and Seaside, and became Astoria’s fifth mayor.

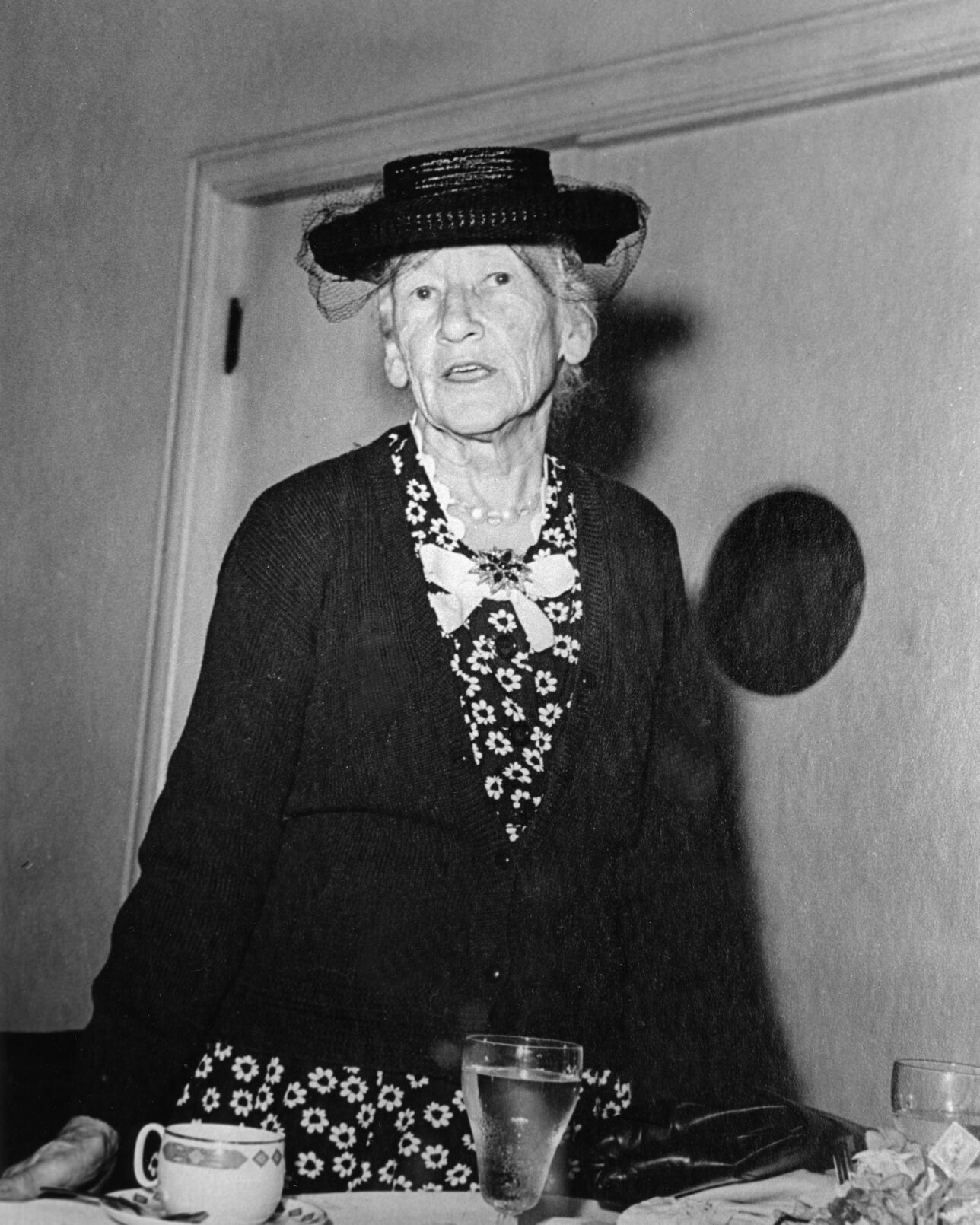

Inez Parker Adams was active in education and civic issues in Astoria.

In 1873, the couple built a three-story brick hotel with 80 rooms, a dining room, parlors and baths named The Parker House Hotel, which remained family-owned until the 1930s.

The couple was passionate about education and helped found McClure School in Astoria. They both served on the school board, with Inez serving as the first female school board member.

Though the couple didn’t have children of their own, Inez’s cousin, Harriet Inez Dunning, was orphaned in 1870 in Montana Territory, and the couple adopted her and brought her to Astoria.

Abigail Scott Duniway, a central driver in the fight for Oregon suffrage, began publishing The New Northwest, a pro-suffrage newspaper, in the 1870s, and many of her editorials were reprinted locally.

Inez and Wilder were supporters of the suffrage movement and led early efforts in Astoria. The first meeting of the Clatsop County Equal Rights Association was held at the Astoria Courthouse in May of 1874, with both in attendance.

In 1896, Scott Duniway invited Parker’s close Astorian friend, Dr. Bethenia Owens-Adair — one of Oregon’s first women doctors with a medical degree — to speak alongside Susan B. Anthony at the First Oregon Congress of Women.

Despite determined efforts, Clatsop County and the state faced staunch opposition to women’s suffrage. The state voted six times on the issue, more than any other state, before it finally passed in 1912.

Inez was one of the few founders of the Clatsop County Equal Rights Association who would live to see women receive the right to vote in Oregon in 1912 and the adoption of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

After Wilder died, Inez spent a few years in California. In 1907, she lived with her sister in Portland. Years later, before she died in 1933, she came back to Seaside to live her last years with her daughter and granddaughter.

Mary Edwards Gerritse

Born in 1872, Mary Edwards, later Mary Gerritse, moved west with her family as a child to settle in the Willamette Valley before homesteading near Manzanita.

The family rented a small house with a cookstove while building a cabin. Settlers depended on supplies that came from Portland by river to Astoria, then to Nehalem. During bad weather, the supply boat couldn’t travel, so neighbors shared necessities until new supplies arrived.

As a teenager, Gerritse was fond of reading. Her favorite authors included Charles Dickens and Charlotte Bronte. When the family ran short on coal oil, she cut kindling into small pieces to make a hearth light to read by.

Mary Edwards Gerritse was an early mail carrier on the often treacherous route between Nehalem and Cannon Beach.

Her father built a one-room cabin that would later receive additional bedrooms and a second story. To finance the homestead, he often had to work additional jobs. When he kept Cape Meares Lighthouse for some months, Gerritse went too, and when he worked at a dairy farm, she milked cows and made butter.

She walked for miles to reach a log schoolhouse, crossing dunes covered with manzanitas and huckleberries. Like most children at the school, Gerritse finished her studies after seventh grade.

She met a sailor from Holland named John Gerritse, who had sailed around the world but, having decided he wanted to stay in the U.S., jumped ship in Astoria.

John took on a mail route from Seaside to Tillamook, a trip that took him a week by horseback. The couple married in November 1888. Mary wore a dark green velveteen dress she made for the occasion.

On a land claim near the Nehalem River, the couple built a cabin. When it caught fire, they returned to Mary’s parents’ home, where their first daughter was born a few months later.

When the baby was a month old, they returned to the claim, but John had to leave for days at a time to deliver the mail. They got two dogs to protect Mary, who was alone with the baby, and a mile away from their closest neighbor.

At first, she was terrified to be in the woods alone, but grew to love it. An encounter with a wildcat prompted her to learn how to shoot a gun. Though the first time she closed her eyes before pulling the trigger, eventually she became an excellent shot.

The family grew, and the Gerritses eventually moved to another homestead near Manzanita so that their children could attend school. As John became busy with farm work, he considered hiring a man to take over his mail route. Though there were few female postal carriers at the time, Mary wanted to try it.

Though the treacherous route involved scaling Neah-Kah-Nie Mountain, Mary handled the service regularly between 1897 and 1902. In some places, the side of the trail fell 400 feet down to the ocean. She traveled it on horseback in all weather.

In 1904, she began carrying mail between Seaside and Cannon Beach, where she and John eventually moved. There, the couple ran a small dairy and Mary helped to found the Cannon Beach Library. Mary died in 1956.