How pinot noir could bridge the ‘rural-urban divide’

Published 12:15 am Thursday, May 16, 2019

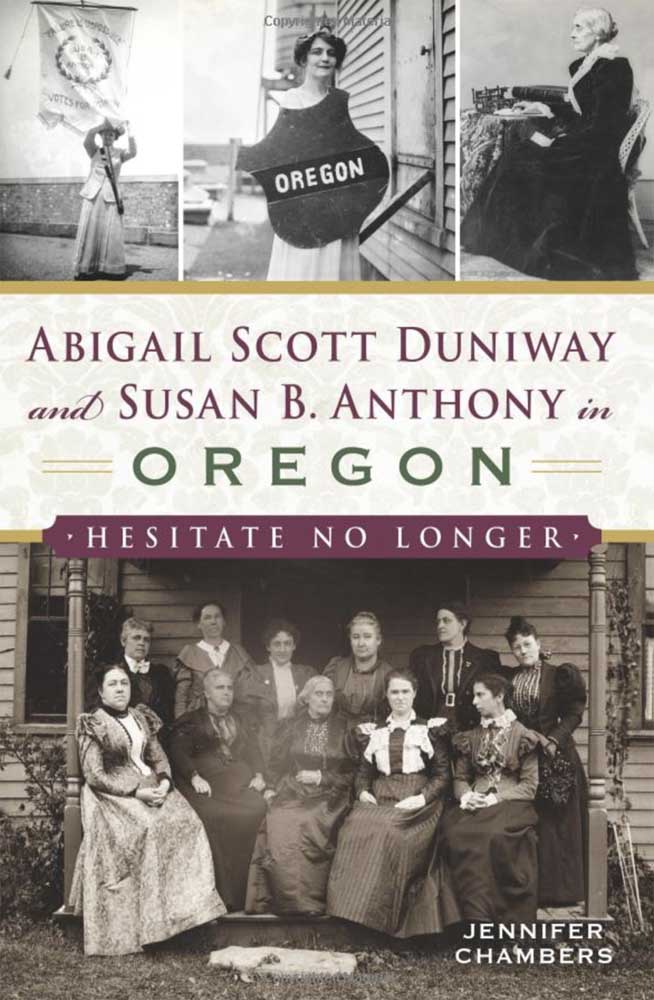

- “Hesitate No Longer” by author Jennifer Chambers chronicles the temperance movement’s history in Oregon.

SEASIDE — May is Oregon Wine Month!

Why not?

Brian Doyle, the great chronicler of Oregon and parts beyond who died in 2016, wrote a whole book to Oregon wine, aptly titled “The Grail: A year ambling and shambling through an Oregon vineyard in pursuit of the best pinot noir wine in the whole world.”

Doyle is the Oregon author I most wish I had met, the former Portland Magazine editor, novelist and bon vivant. I’ve written about his lyrical writing before, best known here for his masterful novel “Mink River” which is in a class by itself in describing the inner life of a small Oregon coastal town.

I like to think we might have shared a glass together: we have so many dovetailing interests: Robert Louis Stevenson (he wrote a whole book about this author, whose “Treasure Island” was one of my favorite books, too.

He was a street basketball aficionado and a dog-lover who passionately believed animals could talk — in his books at least, if not in “real life.” With Doyle’s fulsome imagination, the lines were sometimes blurred.

Doyle employs plentiful adjectives, eschewing all rules and laws of grammar, “direct and straightforward and honest and blunt and powerful and quiet,” as Doyle himself described the boxer Sugar Ray Leonard. His book “Chicago” paints a loving memory of the city in 1978, a year I too inhabited it, and recall the sights, sounds and breath of the Windy City.

In “The Grail,” Doyle pays homage to the hills of the Willamette Valley, where is found the “best pinot noir wine in the world … with the Cascade Mountains glittering snowily to the east and the Coast Range mountains rolling greenly to the west, with a hundred tons of purple-black grapes the size of fingernails roaring by like a murky dusty river.”

California pinot? Bahh, humbug. “Critics of some Oregon pinots have accused them of tasting like silage,” Doyle writes.

When the suffragette movement swept the nation in the late 19th century, many women saw abstinence from alcohol as a cornerstone of the right-to-vote movement; these included the many thousands of members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and National American Women Suffrage Organization, whose passion for breaking the bottle was only exceeded by their passion for the polls.

But Oregon’s Abigail Scott Duniway, a leader in helping Oregon women win the right to vote, took a slightly different tack, Jennifer Chambers writes in a new book, “Abigail Scott Duniway and Susan B. Anthony in Oregon.”

Duniway was described in her day as “5-foot-6, stocky … a forceful, logical platform orator, with a touch of sarcasm and a dash of humor that make her arguments effective. As an impromptu speaker she has few equals.”

Despite her idol Susan B. Anthony’s rigid temperance stance, Duniway earned the disapproval of members of the temperance movement by first recognizing the potential for alcohol abuse. “Too many cases of cruelty, crime and poverty have been traced to the saloon, to expect this conflict to cease until the saloon shall have reformed herself.”

At the same time she recognized the economic importance of “the production, transportation and sale of wheat, barley, hops, rye, apples, peaches, berries, grapes and cherries, from which intoxicants are made.” She offered consideration for the families dependent on these commodities, their sale and production. “Let the blame go to the drunkard, where it belongs, she said. “Let the drunkard’s wife have legal power to protect her home from the debauchery, just as the husband has the power, when so inclined, to protect it now.”

The blowback from the speech, Chambers writes, “was immense.”

Oregon stayed a wet state, at least until 1919 in Oregon and the nation with the passage of the 18th Amendment.

Wine production shut down but resumed in 1933, with Prohibition’s repeal.

According to the Oregon Wine Board, two Salem men John Wood and Ron Honeyman, founded Oregon’s first estate winery, Honeywood, in 1933.

Twenty-eight years later, Richard Sommer launched the state’s “modern era of winemaking,” planting riesling, gewürztraminer, chardonnay, semillon, sauvignon blanc, cabernet sauvignon, pinot noir and zinfandel at his Hillcrest Vineyard in the Umpqua Valley.

David Lett is credited for the first rooted pinot cuttings near Corvallis, in 1965.

These first plantings in the Willamette Valley were followed by a parade of names: Charles and Shirley Coury, David and Ginny Adelsheim, Dick and Nancy Ponzi, Dick Erath, Jim and Loi Maresh, Susan Sokol and Bill Blosser, Philippe and Bonnie Girardet and the Wisnovsky Family. I don’t know any of them, but I’ve seen their names on labels.

According to the 2017 Oregon Vineyard and Winery Census report, wines are grown now through the state, including parts of the Columbia Gorge, Walla Walla Valley and Snake River Valley. Pinot noir holds an unchallenged dominance: with almost 18,000 of the state’s 27,000 acres — about two-third of all Oregon wine is pinot noir, and another 3700 acres produce pinot gris.

Here is how Doyle describes the flavors of pinot noir, with help from his guide, winemaker Jesse Lange of Lange Vineyards: “cherry, plum, raspberry, strawberry, chocolate, smoke, truffles, almonds, cedar, roses, licorice and mint.”

Doyle adds to this: “elegant, velvety, earthy, musty, pungent, fragrant, brilliant, glistening, shimmering, sparkling, aromatic, mysterious, discreet, harmonious, honest, clean, refined, ethereal, romantic and urbane,” among a couple of dozen equally as enticing adjectives.

At one point I would somehow convince myself that I needed to spend $35 on a bottle of wine, with the result I learned to love beer, too.

There are so many good ones in the $8-12 range. At Ken’s grocery, I can find Underwood, Eola Hills and Duck Pond.

One of my favorite wines — alas, from California — is Rex Goliath, named after a 47-pound rooster, “His Royal Majesty, Rex Goliath,” an early-20th century circus attraction. A bottle of pinot noir or cabernet sauvignon goes for $6.49.

When I am ready to dip deeper into the pocket, Gearhart’s Pacific Way Restaurant’s wine list is as well-considered as any, with Cooper Mountain Reserve, Erath Vineyards, Willamette Valley, King Estates, Panther Creek, Archery Summit, Domaine Drouhin Pinot Noir Dundee Hills and The Eyrie Vineyards.

Along with such fine offerings at local restaurants and tap rooms, tastings of Oregon and Washington wines can be found in Seaside at the Wine and Beer Haus, Naked Winery, Buddha Kat and Westport Winery.

Oregon wines may even bridge the daunting “urban-rural divide” in Oregon. In the book “Toward One Oregon: Rural-Urban Interdependence and the Evolution of a State,” the development of specialized agricultural activities like winemaking, beer making and specialized crops offers routes for closing the distance between urban and rural economies.

Portland’s foodie culture values local food, wine, brewpubs and coffeehouses, and “depends on a vital rural periphery,” authors write.

Did I mention that Seaside Wine Walk takes place Saturday, May 18, from 3-7 p.m.?