Bookmonger: Indigenous voices balance U.S. history teaching

Published 9:00 am Tuesday, March 5, 2024

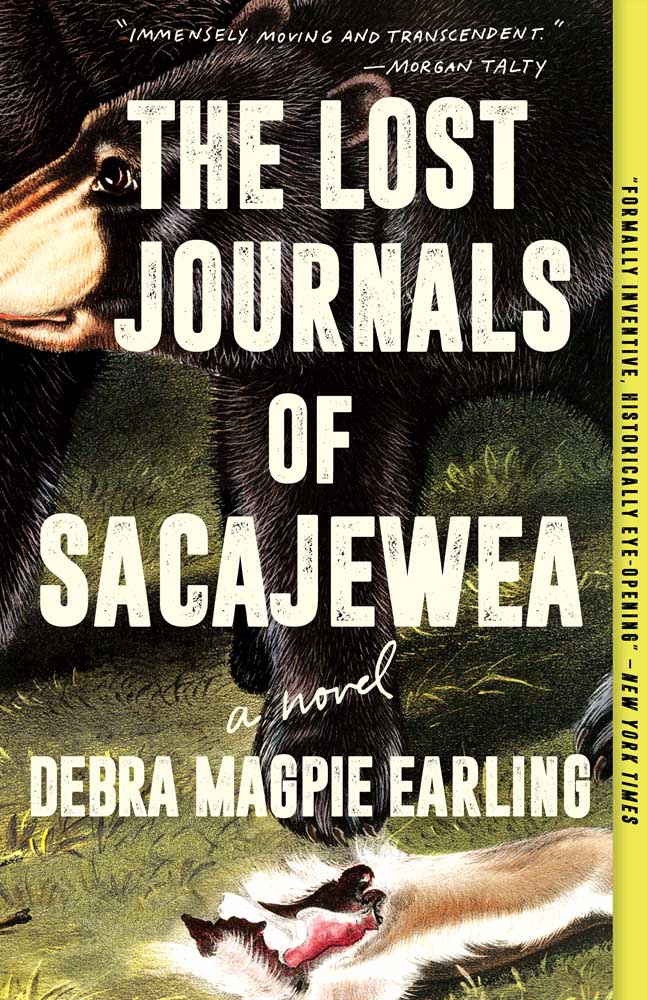

- In “The Lost Journals of Sacajewea,” from Bitterroot Salish author Debra Magpie Earling, Lemhi Shoshone girl who figures as a heroine in the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Many of us who are alive now – Baby Boomers for sure, and perhaps younger generations, too — grew up with a pretty distorted understanding of what life has been like for the Indigenous peoples of North America.

Trending

Yet despite federal government policies requiring that Native Americans be consigned to reservations and boarding schools, and despite repeated misrepresentation via television and appropriation via team mascots, tribal cultures have endured.

Two recent books by Native American authors are a part of this reassertion of Indigenous identity.

Debra Magpie Earling, who is Bitterroot Salish and a University of Montana professor emeritus, has written “The Lost Journals of Sacajewea” — a novel about the Lemhi Shoshone girl who figures as a heroine in our nation’s history, but about whom we know very little.

Trending

“The Lost Journals of Sacajewea” by Debra Magpie Earling

Milkweed — 264 pp — $26

When Sacajewea was still a girl, her mother, Bia, taught her the old ways, what women needed to be able to do in order to survive. These included: “pick berries, dry berries collect, help plants, dig roots, dig potatoes, gather firewood, snare game, gut deer, gut antelope, gut buffalo, gut bear, pound meat … carry children, carry old ones, carry firewood, carry water … ” and the list went on and on.

Sacajewea paid attention, and learned “all good work.”

But when she was an adolescent, her village was raided by the Hidatsa. The enemy tribe killed her parents, kidnapped her, brutalized her and took her hundreds of miles away to their own territory, where they put her to work in their cornfields.

Soon, French-Canadian fur trapper Toussaint Charbonneau acquired her as one of his two enslaved “wives.”

Earling uses a unique narrative style for this work of historical fiction. She incorporates the many different languages that Sacajewea has to navigate — her own native tongue, the languages of other tribes, English, French – and her mother’s frequent expression of disgust, “Puh.”

The author depicts the natural world and the daily toil. She considers traumas glossed over in other more conventional accounts.

Characters include figures from the spirit world as well as historical figures known to have existed. In this telling, Charbonneau is brutal, and Lewis and Clark are coarser and more transactional than our commonly-told mythology would have us believe. Clark’s enslaved Black man York has his own crosses to bear.

Sacajewea bears even more, including her baby boy sired by Charbonneau.

“The Lost Journals of Sacajewea” is severe, revelatory, haunting – and highly recommended.

Another book, “My Name is LaMoosh,” is Warm Springs Tribal Elder Linda Meanus’ firsthand account of growing up near Celilo Falls’ abundant fishery before it was flooded by the Dalles Dam in 1957.

In this book for youngsters, Meanus recalls other Indigenous practices that likewise were in danger of being obliterated, but that were kept alive due to the perseverance of her elders.

Relating this tale in a warmhearted way, Meanus shows how tribal identity and cultural expressions are closely tied to the landscape.