A historic house in a historic village

Published 11:45 am Wednesday, March 20, 2019

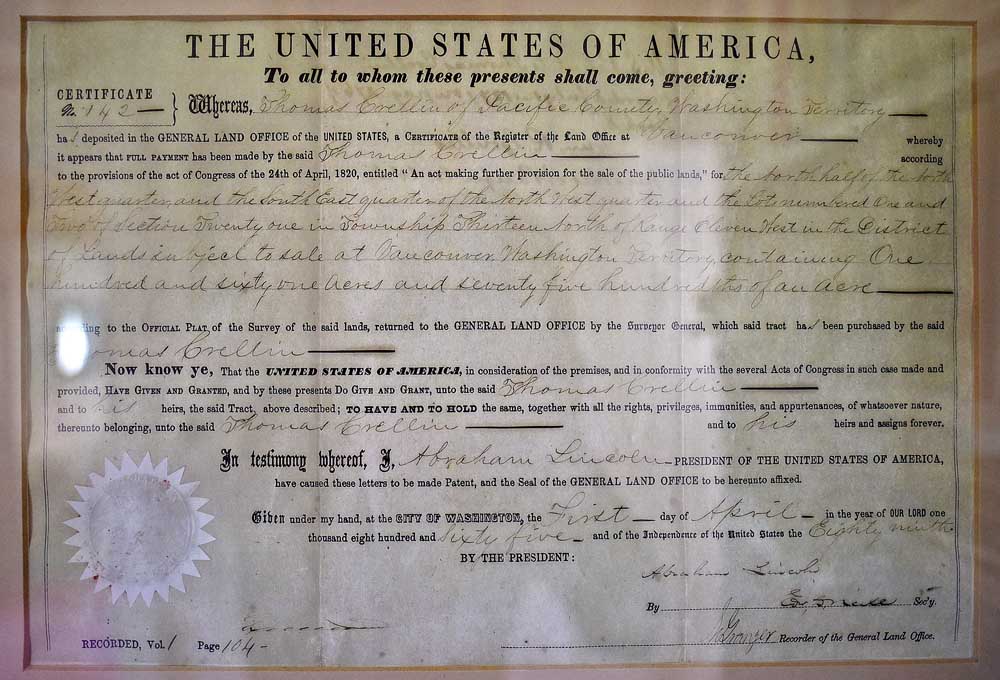

- A document signed by Abraham Lincoln pertaining to the Espy House is now displayed on a wall in the main living room. Lincoln's signature can be seen near the bottom middle of the photograph.

Sydney Stevens, of Oysterville, Washington, is celebrating a 150th birthday this year.

It’s not her birthday, of course. It’s the birthday of something in her family: her home.

“When I say ‘in the family’ I mean that in every sense — fanciful and otherwise,” Sydney wrote in her daily blog, Sydney of Oysterville.com.

“These walls do talk to us — their scars and patches have recorded many stories from long ago. We also know that the house is happiest when there are parties and concerts and events here — the house loves people … We consider the house a beloved family member.”

Sydney, the great-granddaughter of Robert Hamilton (R.H.) Espy, co-founder of Oysterville, owns the home, with her husband, Nyel.

Three generations of Espy descendants have lived in the home in the tiny town on the Long Beach Peninsula’s north end. Harry, the son of R.H., moved there first, then Sydney’s parents and, finally, Sydney and Nyel.

Built in 1869 of redwood lumber that came by ship from California, the stately two-story home faces Willapa Bay. Gingerbread decorates the top of the white house with blue-green trim, and the house is surrounded by an expansive lawn, where many croquet games have been played through the decades.

Architecture ahead of its time

R.H. and Isaac Alonzo Clark, who Espy met on a westward-bound wagon train, founded Oysterville in 1854. While other pioneers discovered gold in California, Espy and Clark discovered their “gold” in the oyster beds of Shoalwater (now Willapa) Bay.

Oysterville became a boomtown, with a population of about 250. Today, it is a quiet National Historic District with a full-time population of 14.

The men built a 10-foot by 12-foot log cabin to live in. After Clark married and moved out, R.H. constructed his own home, known as the “big red house.” It also remains in the family.

Meanwhile, another oysterman, Tom Crellin, received a land grant, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, and built the home facing the bay. Sydney still has the signed grant.

When Crellin and his family moved to San Francisco, R.H., a staunch Baptist, bought the home in 1892 for a parsonage. He had already donated the land across the street and $1,500 to build a Baptist church.

Until then, the circuit “sailing” ministers, who traveled to coastal towns by boat, had stayed at R.H.’s home when they were in town. One stayed for 12 years.

“He was sick of having those preachers staying at the red house,” Sydney said, laughing.

Six ministers lived in the parsonage. The wife of one minister mysteriously drowned while she and her husband were sailing in the bay. Over the years, several people have reported hearing a woman’s sweet, ghostly voice singing hymns in the former parsonage, according to Sydney.

R.H.’s son, Harry, a state senator, and his family moved into the home in 1902.

Although she hasn’t seen the house plans, Sydney believes Crellin’s father brought them from the Isle of Man when the family settled on the peninsula. When Oysterville was named a National Historic District in 1976, architectural historians who noticed details about the home, including the low doorknobs, told Sydney’s parents that the home was “state of the art in England in the 1860s.” Usually, home styles in the West were behind the East Coast by about 20 years.

“They said that this predates anything else that is on the West Coast,” Sydney said.

The old and the new

The home’s first rooms included a parlor, sitting room and kitchen on the ground floor. In a cubbyhole under the stairs, a clawfoot bathtub remains from those early days. Four bedrooms were on the second floor. Bathrooms — including a commode off the kitchen — eventually replaced the outhouse. Electricity arrived in 1936.

“The house ended here,” said Sydney, indicating a wall on the west side of what was the kitchen and is now Sydney’s library.

Beyond that wall were the outbuildings — a woodshed, a meat-hanging room and laundry.

A brick fireplace from the old kitchen still has iron brackets where pots probably hung over the fire.

But when fire destroyed part of the kitchen in 1915, it was, Sydney said, “the year my grandmother moved west.”

The “outbuildings” on the west side were incorporated into the house and turned into a sitting room, dining room and kitchen. The dining room has original dark tongue-in-groove paneling and built-in cabinets from 1915, while white beadboard covers the kitchen walls. Grandmother’s pie cooler was converted into a cupboard, and a gas stove replaced the wood stove.

The old kitchen became a library, something Sydney’s grandmother had always wanted.

When Sydney and Nyel moved to the house in 1998, the first thing they did was to insulate it. But most of the house remains as it did when her grandparents, and then her parents, lived there.

The parlor ceiling is covered with the original wallpaper from 1869. The front window, which looks out to the water, and the bay window, where Sydney’s grandparents used to place their Christmas trees, are the original glass.

One of the home’s two coal-burning fireplaces heated the former parlor, now the Stevens’ bedroom. Enclosed in marble, the fireplace matches the one in an upstairs bedroom. Neither fireplace currently works.

Sydney’s parents built two bathrooms behind the parlor and added a large closet. Nyel and Sydney removed one of the bathrooms and turned the closet into an office, where Sydney writes a daily blog, newspaper columns and books about local history.

‘Like a member of my family’

On the opposite side of the hall from their bedroom is the family room.

“When my mother was a little girl, this room was the nursery,” Sydney said. “There was a huge homemade Murphy bed on this wall,” she added, pointing to the south wall. Three children slept in it during the winter because the downstairs was warmer than the upstairs bedrooms.

Her parents replaced the original wood stove with a fireplace. Over the mantel is a painting of Sydney’s grandparents sitting in that room. The painting, which commemorated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1947, shows her grandmother with a typewriter in her lap. Her grandfather (“Papa”) sits in front of the wood stove, holding a letter.

“It was so typical,” Sydney said. “Papa would go to the post office in the morning to get the mail, and he would come home and read the mail to my grandmother … After lunch, she would sit and write to her children. When she knew she was losing her sight, she learned to type. My grandfather had given her a very small typewriter, and she would put it on her lap and type.”

Family photos dating to the late 19th century cover the walls in the front hall, where a steep, curved staircase leads to the bedrooms. A bedroom wall contains a framed collection of paper dolls, circa 1887, that belonged to Sydney’s grandmother. Nearby, a glass case features dolls from the 1930s to the 1950s given to Sydney by her uncle, who traveled on business.

A tiny bedroom in the back was reserved for maids or children. Another bedroom brings back special memories for Sydney, who, as a teenager, would crawl out the window to the low-sloping roof below to meet her friends at night. Sydney was following a family tradition: Her mother did the same thing when she had the room as a young girl.

With the home’s 150th anniversary approaching next September, Sydney hopes to invite the public to celebrate. She wants to honor the home that has meant so much to her.

“It’s like a member of my family,” she said. “It’s my connection to the generations that have gone on before.”