Bookmonger: Living landscapes of the Northwest

Published 9:00 am Wednesday, March 22, 2023

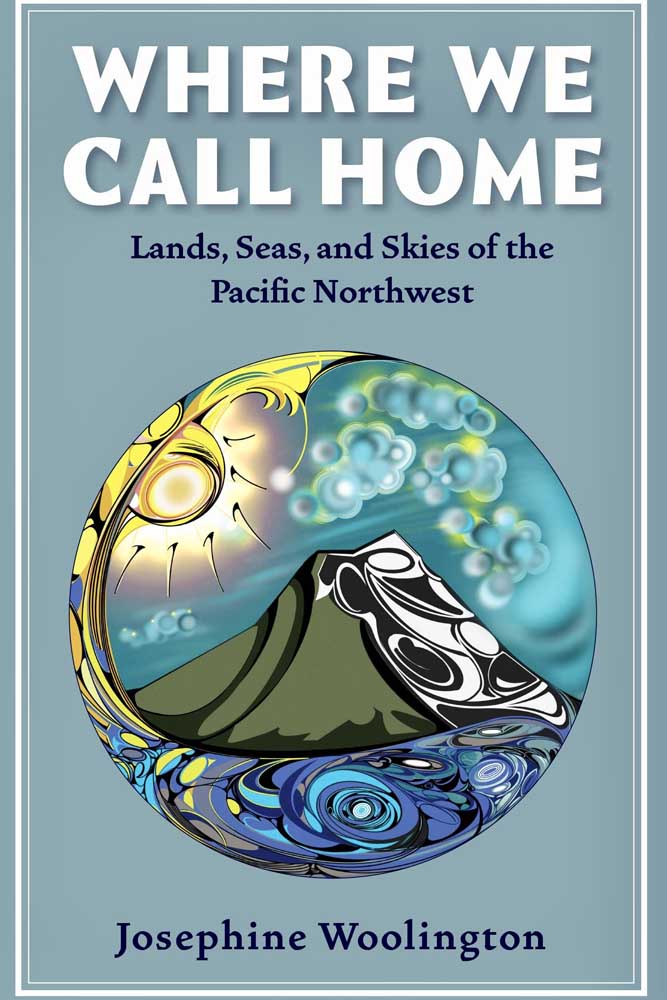

- “Where We Call Home” is by Josephine Woolington.

Kudos to Portland-based freelance journalist Josephine Woolington and Portland State University-based Ooligan Press for “Where We Call Home,” an exploration into the landscapes, waterways and skies of the Northwest.

Trending

In 10 essays, Woolington focuses on biological and geographical features that are emblematic of the region. She dives into scientific research, Indigenous knowledge, and hands-on personal experience to satisfy her curiosity on topics from bumblebees to clouds to gray whales.

This book was conceived in the throes of the coronavirus pandemic. Compounding that crisis, here in the Northwest we also were confronted with climate fires and the pall of smoke that choked so much of our region. These crises prompted Woolington to reconsider life as she had always lived it.

“Where We Call Home” is tinged with those realities. At a time when we all were being encouraged to self-isolate, Woolington began to think more deeply about some of the features she always had taken for granted in the landscape surrounding her.

Trending

“Where We Call Home” by Josephine Woolington

Ooligan Press — 272 pp — $24.95

“The Naturalist’s Companion” by Dave Hall

Mountaineers — 208 pp — $19.95

In her research, and in her interviews with folks ranging from tribal leaders to university professors to artists, the author realizes that the particular life forms she’s looking into — whether camas flowers or coastal tailed frogs — all have been impacted by human activity since long before this.

And while the practices of Indigenous people did involve hunting and harvesting and manipulation of the environment through controlled burns in forests and on prairies, a fairly balanced relationship between human and other species had been sustained throughout millennia until white colonizers came to the region and engaged in practices involving significant resource extraction and disruption of natural landscapes.

Even well-intentioned, if belated, attempts at environmental conservation — such as fire suppression, encouraged by the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot — had detrimental consequences because they were not grounded in a thorough understanding of all of the factors that figure into a healthy ecosystem.

Post-quarantine, Woolington ventures out into the field. She hikes through the Hoh Rainforest (“considered one of the quietest places in North America”) and visits various nesting and resting areas for sandhill cranes, “calling in their thunderous voices,” from Sauvie Island to Malheur Lake.

Persnickety readers may notice that the proofreading for “Where We Call Home” could have been sharper — errors like mistakenly using the verb “lay” instead of “lie,” misidentifying Slade Gorton as a Congressman instead of a United States Senator, and there are more examples — should have been caught and corrected before publication.

However, Woolington’s essays provide wide-ranging insights into each species considered, and her decision not to refer to creatures as “it” (because they are living beings, not objects), also makes the writing feel personal and accessible.

A quick note — if you’re inspired by Woolington’s forays and want to conduct some of your own, check out “The Naturalist’s Companion,” a new field guide by Dave Hall from Mountaineers Books, on how to seek wildlife encounters in a safe and ethical way.