‘Magdalena Mountain’: A review of Pyle’s first novel

Published 6:15 am Monday, September 10, 2018

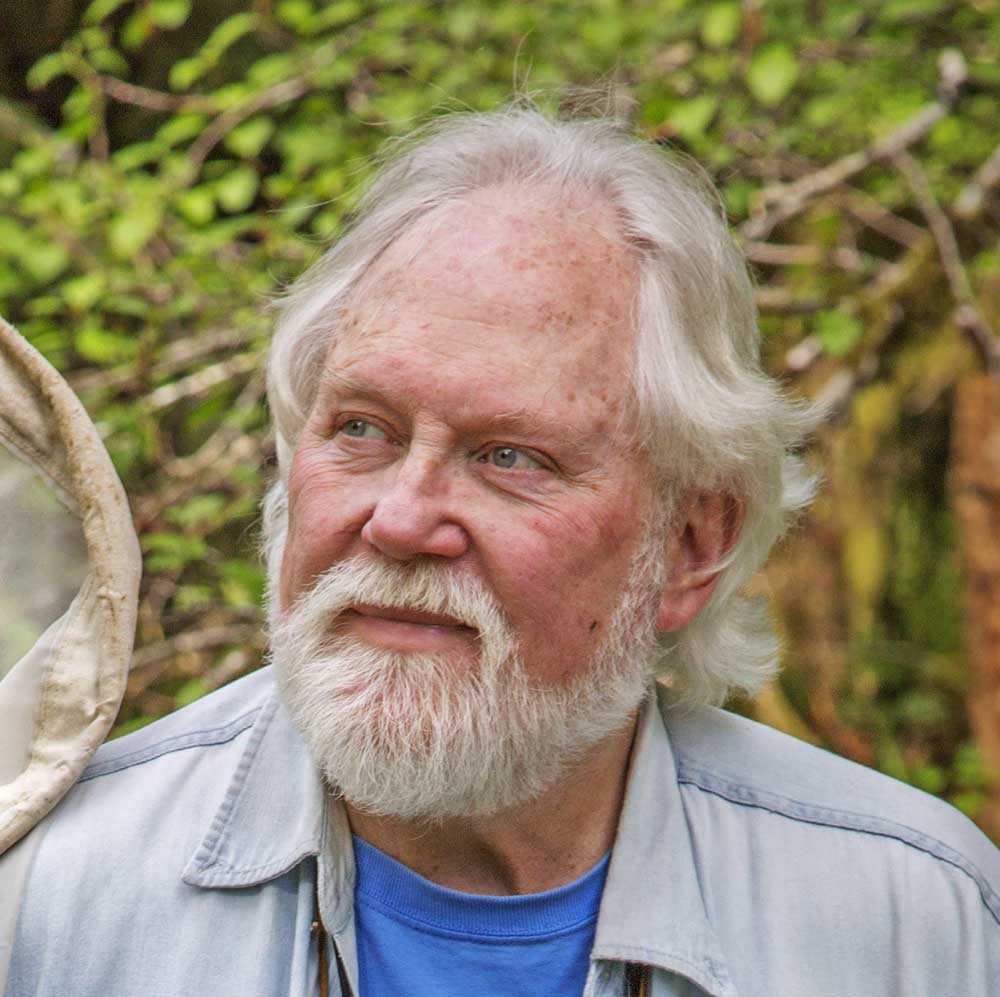

- Lepidopterist, scholar and Grays River author Robert “Bob” Michael Pyle has just published his first novel, ‘Magdalena Mountain.'

The historical fiction author Molly Gloss, of Oregon, says, “Fans of Robert Michael Pyle’s nonfiction will not be surprised to find that his first novel abounds in details of the natural world — lovingly described plant and animal and insect life across the changing of the seasons on a remote Colorado mountain.” Yup.

A couple of years ago I had the great good fortune of sitting with Bob in an extended afternoon-evening sipping wine on his front porch and solving the worlds problems — which, in case you’re wondering, quickly became unsolved again. I noted then that in response to my email about directions to his house, Bob wrote, “I’ve no idea about GPS … does that stand for Great Plover Society? Turn right at the giant oak.”

This, in a nutshell, tells you all you need to know about our local and national treasure: He’s a brilliant student of nature with a quick wit and a whimsical sense of humor — all characteristics clearly evident in his first (and we can only hope not last) novel “Magdalena Mountain.”

When I picked up Bob’s recent book, stashed in a secret hidey-hole at the Chinook Observer office, I had some idea of what I might find between its covers. I’ve read the marvelous, heartbreaking and award-winning “Wintergreen” (Scribner, 1986) describing the devastation of logging to our damaged land; “Sky Time in Grays River” (Houghton Mifflin, 2007) about the season-by-season unfolding of lives of the creatures populating, almost literally, his backyard; and “Mariposa Road: The First Butterfly Big Year” (Houghton Mifflin, 2010) chronicling Bob’s travels and misadventures documenting as many butterflies as possible.

His nonfiction prose is lush with detail and emotion, so I expected no less when, in 2014, Bob published his first chapbook of poetry, “Letting the Flies Out” (Fishtrap, 2011), followed shortly by a full-length book of poems, “Evolution of the Genus Iris” (Lost Horse Press, 2014). As Bob said about two prominent poet friends, Pattiann Rogers and Alison Deming, “I listened to them a lot and I read a lot of poetry. I read and read. And I began to realize, and they told me, that my prose was poetic. I found that I had an ear for cadence.” I’d say that’s an understatement.

Now Bob has tripped the light fantastic and written a rollicking novel with a sprawling set of characters — both human and entomological. In fact, of all the stars in “Magdalena Mountain,” I found myself most waiting for the continuing story about our Erebia magdalena. (Erebia is a genus of 90 to 100 species of “brush-footed butterflies, family Nymphalidae, dark brown or black in color.”)

We follow this Erebia throughout his life — through his transformation to butterfly, to escape from a swallow’s beak, to finding a mate, to his nearly witnessing a crime, to his death on the scabby rocky slope where his whole existence has been spent.

Meanwhile, in alternating chapters, is the story of the human cast: James Mead, a young Yale student of ecology; professor George Winchester and his mega-roaches; Mary Granville, a spiritual savant; Oberon, the head of a monkish group of Pantheistic environmentalists called the Grove; Attalus, an angered and misogynistic Grove aberrant; October Carson, a peripatetic butterfly collector and journal writer; Bagdonitz, the leader of the Flying Circus, a roving band of biology students; and … well, I don’t want to give away the whole story.

When Bob manages to bring them all together, in the climactic final chapters, to the question “What’s the occasion?” Oberon says, “Storm, lightning, attempted murder, general mayhem …”

So don’t expect a tidy tucked-in tale with profound interior monologues and a subtle slow-moving plot. This novel is a fast-paced lighthearted frolic, equal parts nature study, biological inquiry, mystery of identities and eco-feminist manifesto lite, with dark corners providing tension.

Bob’s strength is his stunning descriptions of the natural world and his deep knowledge of the fauna and flora.

Less convincing for me were parts of the dialogue, especially when the female characters speak up. These seem almost asides meant to nudge the plot along, or fill in some theoretical framework, rather than discourse emanating from character.

Humor and wit bubble up throughout, aided by the vast range of Bob’s knowledge of literature and biology. The love scenes — this book has everything! — are sensual meanders often set in terms that reflect nature.

The occasional unlikely plot twists — well, we forgive those because we simply want to enjoy the story as it races along from Boston to Magdalena Mountain to New Mexico and back. Do we need the side story of the loss of James’ sister and his guilty and remorseful relationship to his mother? Maybe better to deepen James’ relationship with Noni Blue, give her more dimension and perhaps a different name. (“Noni” is the street name for a knobby, sour fruit, a food of last resort in the Hawaiian islands.)

I place “Magdalena Mountain” in the same file as my favorite of Shakespeare’s romances — “Cymbeline” and “The Winter’s Tale” — where a mash-up of realism and whimsy combine for surprises and morbid twists that land on their feet in the light of day. In good Shakespearean tradition, Bob gives us disguise, lovers thrown asunder, lovers reunited, good overpowering evil and the kind of satisfying operatic crescendo in which everyone shows up onstage just before the final curtain. I read the book straight through in two nights — couldn’t put it down.

Bob has pulled yet another genre — and another funny, lovable, well-mannered, exquisitely detailed pika — out of his hat. I highly recommend this romp through the natural world of the Colorado Mountains, and through the hearts and minds of a colorful, diverse and intimately connected kaleidoscope of characters.