The Liberty Theatre’s comeback

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 6, 2018

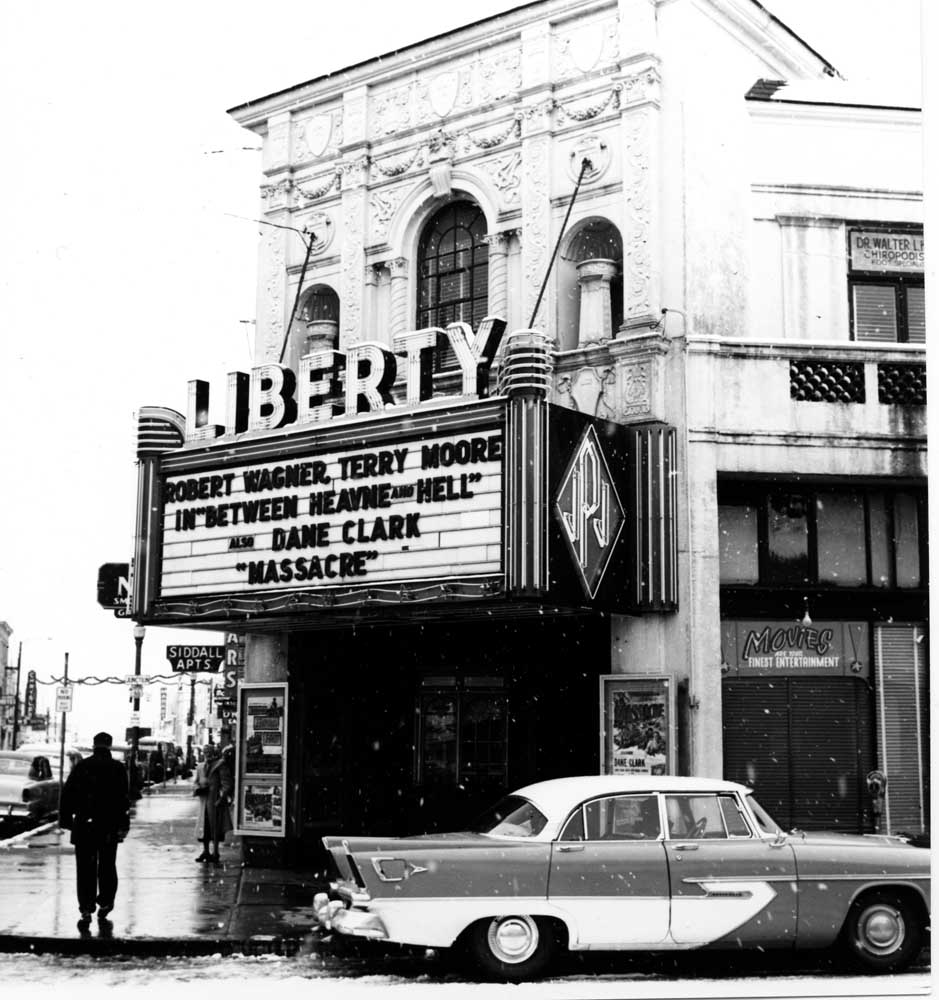

- The Liberty Theatre’s original glass canopy was replaced by a movie marquee in the 1950s. This 1956 photo shows the marquee with a Plymouth Belvedere in front.

From rocky, raucous beginnings in 1811, Astoria grew exponentially, yet citizens were still decrying its rough atmosphere a century later. One resident wrote in a letter to the Astorian Evening Budget in 1915 that it was a city of “mass contradictions and magnificent possibilities … tasty homes hemmed in by a jumble of shacks which, in most places, would have been eliminated ages ago as fire traps.”

That “magnificent possibility” would eventually come to fruition, though at a terrible cost. As cynically predicted by the disgruntled writer, the fire of 1922 decimated Astoria, obliterating nearly 30 downtown blocks.

But the fire became a rallying cry to rebuild, and by 1925 the construction of the Astor Building complex, with its offices, stores, dance studios, and centerpiece — the Liberty Theatre — not only signified the city’s revival, but created an architectural gem.

UP FROM THE ASHES

The Portland firm Bennes & Herzog, known for their extravagant movie palaces, combined elements of Romanesque and Italian-Renaissance styles to construct Astoria’s ornate 700-seat vaudeville stage and motion picture theater.

Tuscan Doric columns, Moorish arches, gilded friezes, festooned pilasters, and a magnificent Wurlitzer organ with cathedral chimes weren’t quite enough ornamentation. The architects also commissioned 12 large mural-like canvases depicting Venetian canal scenes by Northwest artist Joseph Knowles, and a breathtaking, 8-foot-tall, 1,200-pound, iron-framed paper-and-silk Chinese lantern-styled chandelier by Portland artisan Fred Baker — all glamorous touches meant to transport the audience to a more romantic world.

High school students worked as ushers wearing uniforms of yellow and black blazers and slacks, complete with classic pillbox hats. Not a bad deal for young entrepreneurs who earned 27 cents an hour, plus tips.

Vaudeville acts and silent movies were staples of the new venue, which also drew big-band names like Guy Lombardo and Duke Ellington, and headliners that included Jack Benny. It is said that even Al Capone attended an evening’s attraction.

During World War II, the theater was packed with viewers eager to watch newsreels and buy War Bonds. Vaudeville remained the core attraction for 25 years, but as movie “talkies” arrived, it lost its appeal. The original exterior glass canopy was replaced by a modern double-feature neon marquee, and the Wurlitzer, now obsolete, was removed. A concession stand was installed in the lobby so patrons no longer had to walk around the corner to Kildahl’s café for popcorn, sodas, and candy.

Saturday matinees in the 1950s featured newsreels, cartoons, and serials like “Superman” or Westerns, a boon to parents to get the youngsters out of the house.

“Every Saturday my parents gave me 50 cents — 25 cents for the movie and 25 cents for popcorn and candy,” remembered local resident Lois Barnum, who grew up in Astoria. “Upstairs were dance studios where most kids in town took tap, ballet, or jazz classes. In the 1960s, when I was in high school, there were rarely first-run movies, and the same feature ran for two or three weeks. If I had different weekend dates, I’d end up seeing the same movie twice, and sometimes three times. Going to the theater was really the only thing in town to do.”

Until attractions in Seaside or Long Beach, Washington, provided competition, the Liberty Theatre was the main source of entertainment in the region, and regarded by many as “Astoria’s living room.”

DOWNWARD SPIRAL

Despite the Liberty’s reputation as a valuable entertainment hub, within a couple of decades, the theater went into decline.

“The theater was in the wilderness for a number of years,” Steve Forrester, former publisher of The Daily Astorian, said of the 1980s and early 1990s. “The absentee landlord, Edward Eng, used the complex as a tax break and let the theater go to near ruin. There was no heating and no cleaning, and people were living behind the stage curtain — you sometimes heard them, but you never saw them.”

The upstairs balcony was partitioned into two plywood boxes with little sound-proofing, according to Brenda Penner, a 30-year Astoria resident. “At least a thoughtful carpenter protected the Venetian mural paintings by covering them with Plexiglas. There wasn’t a single row where seats were not broken or missing. Your shoes would cling to the sticky floors, and the main screen had a huge blotch on it, probably the impact of a thrown Coke.”

It was so cold in the theater, Penner recalled, that people had to bring their own blankets to stay warm. What’s more, “there were peepholes in the walls of the women’s bathroom. It was so gross, we finally quit going,” she said.

Leslie Duling McCollom, a student of Astoria High School in the 1990s (and niece of this author), said the theater in her youth was “yucky and spooky.” However, she said, “it was quirky and weird and fun, and one of the few places in town to hang out as teens.”

The building suffered from neglect — the interior a wreck and the exterior an eyesore — and many residents feared the Liberty would become too dilapidated to save.

TAKING THE LIBERTY

In 1992 a group of civic leaders, including Forrester, Michael Foster and Hal Snow, stepped in to save the theater by forming a nonprofit organization, Liberty Restoration, Inc. They attained national status as a “Save America’s Treasures Site,” and purchased the theater in 2000 with $1.3 million from the city’s Astor East Urban Renewal District funds. And the monumental task of restoration began.

Volunteers began to clean and remove alterations — finding that, remarkably, no major structural damage had been done, and the restoration would be mostly cosmetic. Mounds of what Forrester calls “fossilized popcorn” were removed from the orchestra pit light troughs. Knowles’ mural paintings were painstakingly revived from years of nicotine stains, the original exterior glass canopy was replicated, and the Chinese lantern chandelier was restored at a cost of $100,000 alone. Emigrant Romanian artisans, experts in decorative plasterwork, restored and reproduced medallions that were later gilded by Clatsop Community College historic preservation students.

The challenge was not only restoring the theater to its former self, but simultaneously updating it into a contemporary performing arts center, a feat that required raising, as Forrester said, “only a few million more.” Through grants and donor gifts L.R.I. did manage to raise the $7.5 million cost of the renovation.

Finally, in 2005, the glamor and excitement of 1925 was replicated with a sellout crowd for the grand reopening night.

RISEN AGAIN

Today, the Liberty is once again considered “Astoria’s living room,” a premier theater for the arts featuring regional and national performing artists, including music, theater, dance, and diverse cultural performances, such as the widely popular FisherPoets readings.

More than 120 volunteers help to keep the theater running — from ticket-takers, to ushers, to the folks manning “Chez Jo’s” concession stand (though without the classic blazers and pillbox hats). Theater Director Jennifer Crockett and Artistic Director Bereniece Jones-Centeno — who are musicians themselves — understand what widening the venue’s scope and bringing new sounds to the Liberty can mean.

A Classical Series has been launched, and free events every month pack the house. They’re passionate about fostering education in the arts and access to all types of cultural experiences, especially for children. The second-floor former dance studio spaces are used by visiting orchestra members, musicians, and dance troupes, who work with local high school students at no cost. Crockett hopes to encourage locals and visitors alike to feel that the Liberty is not an elite venue, but a place for everyone.

“Things are going well,” Crockett said. “Donors are stepping up and sponsorships are filling gaps, although funding for a wide variety of performances, mounting productions, and workshops remains a challenge. But people seem really excited about the theater, and I hope that this is a start of a longterm love affair.”

A SAVED VENUE

One person who shares Crockett’s sentiment is Israel Nebeker, the songwriter and frontman of the indie rock band Blind Pilot who now serves on the Liberty board.

“I grew up going to movies there when it was spooky and cool,” he said. “It’s a building I’ve always known, and that first night playing there was a pretty big moment. Just like playing on ‘Late Night with David Letterman,’ performing at the Liberty was a dream come true. Every time we play there, even now, it’s significant for me; it makes me so happy. And it’s one of the best-sounding rooms I’ve been in: The sound is so alive and clear.”

On the road, Nebeker has seen too many theaters that were once magnificent now shut down or demolished, he said. “It’s heartbreaking, the stories about how towns have lost these places. But Astoria didn’t let this happen. It means a lot to me that Astoria could save this great venue.”

A century after that peevish 1915 letter to the editor, Astoria is once again striving to realize its many magnificent possibilities. One thing is certain: No cynic can complain about the splendid restoration of the Astor complex and the historic Liberty Theatre.

The Liberty Theatre is located at 1203 Commercial St., Astoria, Ore. 97103. For tickets and information contact the website libertyastoria.org or call 503-325-5922.