Bookmonger: The problems with border policies

Published 9:00 am Monday, February 17, 2025

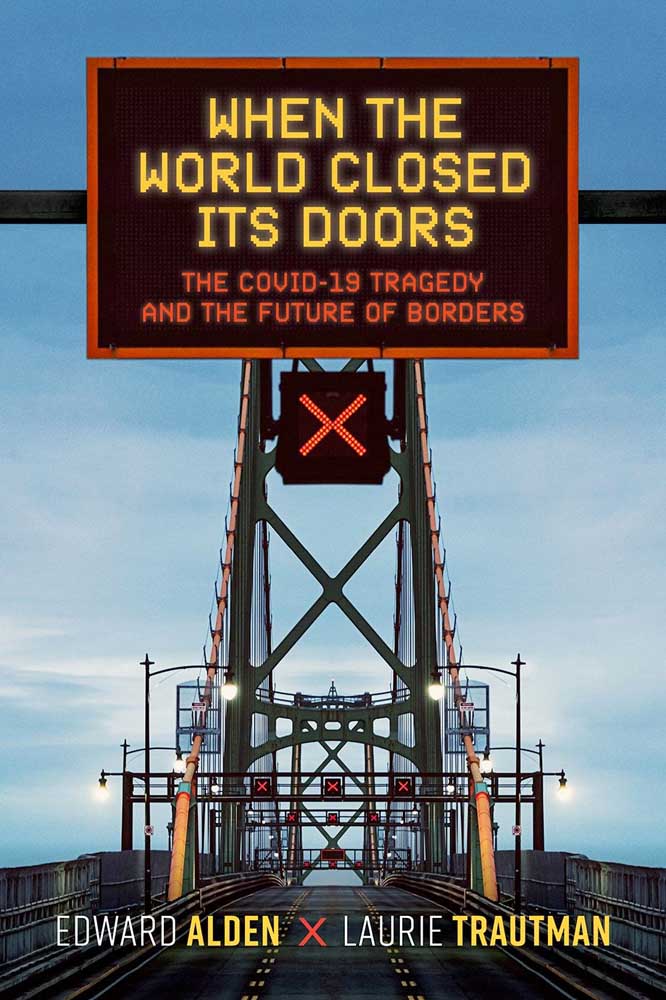

- Co-authors Laurie Trautman and Edward Alden argue for a more comprehensive approach to border policy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Last year, international travel rebounded to nearly its pre-COVID-19, all-time high levels: some 1.4 billion people crossed a foreign border, according to UN Tourism, an agency sponsored by the United Nations.

So the timing of the publication of “When the World Closed Its Doors” might seem a little off, except for the recent aggressive push of some of the world’s most traditional welcomers of immigrants — including the United States — to harden their borders further and launch sweeping deportation efforts.

Co-authors Laurie Trautman and Edward Alden provide wide-ranging context, largely but not solely informed by mistakes made during the COVID pandemic years, to suggest that international systems of travel, migration patterns and displacement factors like war, genocide and climate change require a more comprehensive and humane approach than simply tightened border restrictions.

This week’s book

“When the World Closed Its Doors” by Edward

Alden and

Laurie Trautman

Oxford University Press — 344 pp — $35

After earning a Ph.D. in geography from the University of Oregon, Trautman now serves as the director of the Border Policy Research Institute at Western Washington University.

Alden’s portfolio includes more than three decades of work in journalism and academia. He is now a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and has been a visiting professor at Western Washington University since 2019.

Trautman and Alden serve a global perspective and cut no one any slack. They provide anguishing examples from individuals around the world who were adversely — and, the authors maintain, unnecessarily — impacted by overly draconian border shutdowns during COVID that were based on politics rather than science, common sense or compassion.

There’s the story of the pregnant but unmarried New Zealand woman who was working in Qatar when a sympathetic doctor told her it was illegal to be pregnant and unmarried in that country. Unable to gain permission to get back to her own country, she fled to war-riven Afghanistan, where her journalist boyfriend was based.

“When the Taliban offers you — a pregnant, unmarried woman — safe haven, you know your situation is messed up,” she reflects.

There are other stories of couples separated by nationality, grown children prevented from tending to their dying parents, or parents separated for more than a year from their young children due to strict pandemic restrictions. Merchant sailors and cruise ship workers were stuck on their ships for months on end, stranded in their windowless cabins with minimal food.

Yet there were exceptions made for other “essential workers,” the authors point out, and capitalist activities like international supply chains were never shut down in the way that human-to-human relationships were.

After enumerating how COVID-era border restrictions had multifaceted global impacts, the authors urge that policymakers around the world move beyond political knee-jerk responses and put more effort into figuring out how to take into account the many other considerations — demographic, economic, social, and emotional — in designing clear, compassionate, and workable travel and migration policies moving forward.

They close with a warning that the next pandemic will appear before we know it, yet we haven’t done enough to review lessons learned from the last one.