Bookmonger: Tales of homes and hope lost

Published 9:00 am Wednesday, January 8, 2025

- In “Stealing Home,” Western Washington author Sharon Hashimoto addresses generational impacts on Japanese Americans after incarceration during the World War II era.

As we enter into this new year, we need to be mindful that there are hard times — currently, and ahead — for folks across the globe who are being displaced from their homes by famine, poverty weather events or violence — frequently through no fault of their own.

Addressing their desperation with compassion is always the appropriate response, but there are far too many places where compassion will be in short supply.

Sadly, as Tukwila, Washington, writer Sharon Hashimoto demonstrates in her latest published work, this is nothing new.

Best known as a poet, Hashimoto turns to short stories to address the compassion gap in a targeted collection called “Stealing Home.” Drawing from the mid-20th century Japanese-American experience, she explores the generational impacts of the World War II-era incarceration of people with Japanese ancestry along the West Coast.

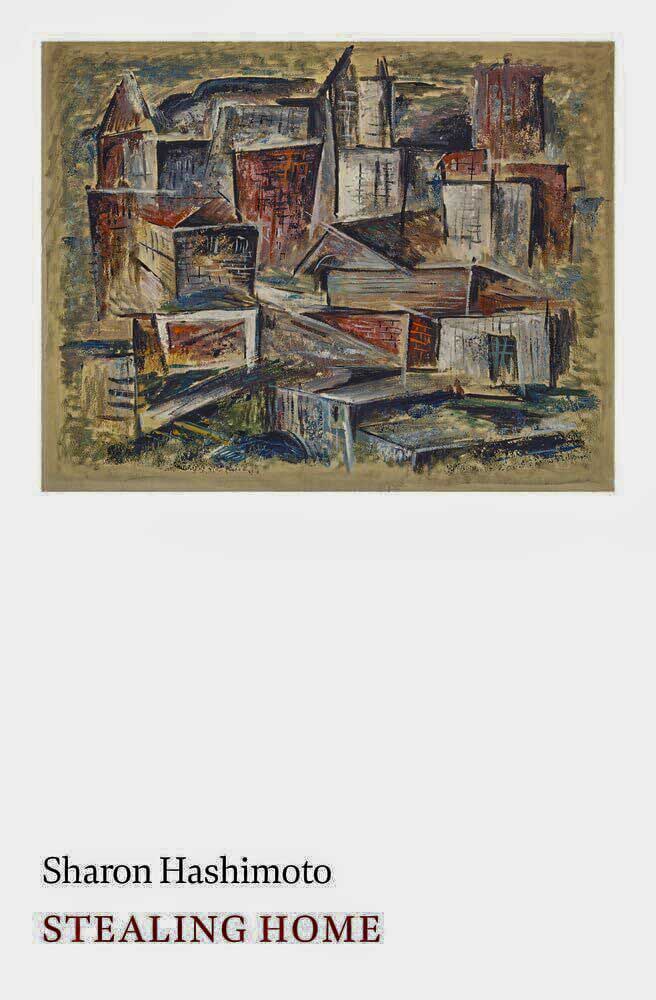

“Stealing Home” by Sharon Hashimoto

Grid Books — 180 pp — $22

In a story set in 1950, Hashimoto invokes the blues song “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” as the musical theme for an older couple struggling to subsist after World War II has ended and they’ve been released from one of the camps.

The husband has found work as a night janitor, and the wife picks up piecework whenever she can at a local glove factory. But a day at the beach to harvest shellfish and a jolting bus ride back home only underscore the twin hardships of poverty and discrimination that the couple continues to face.

Another story, “No Further Than You Can Throw,” illuminates the uneasy pecking order of racism, and the subtle way that prejudice is passed down through the generations. When a Japanese American dad complains about his Filipino co-workers on the assembly line at Boeing, the man’s son echoes the “othering” by preventing a Black classmate of his 8-year-old sister from walking her to school.

Hashimoto also writes stories that explore the tricky power dynamics within families. Parents favor one child over another. Grown siblings bicker over how to care for their parents. Spouses become distracted, or complacent.

In the story called “Sworn,” only the young son is bilingual, so he is tapped to accompany his mom to the doctor to try to help her convey her sensitive medical issues.

There is a baker’s dozen of stories in this collection, and the tales that tug most at the heartstrings are the ones of elders who had survived the perils and/or indignities of World War II, then endeavored to rebuild their lives after so much had been taken away from them, only to struggle in their later years to remain relevant in the lives of their children and grandchildren.

With her poetic ability to condense so much into a single word or phrase, Hashimoto cuts to the quick with actions and imagery that convey isolation, yearning, or loss. Home is where the heart is — but what if those hearts are broken? Or hardened?

The stories in “Stealing Home” examine so many facets of the bitter legacy of displacement. These are cautionary tales.