Bookmonger: A movement spawned along the Columbia

Published 9:00 am Monday, September 23, 2024

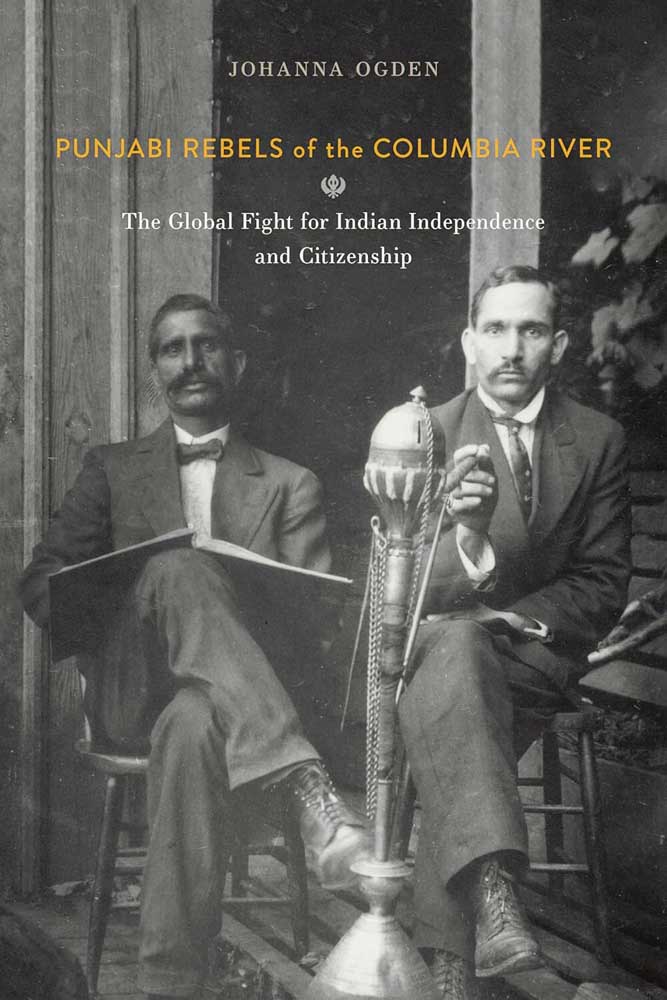

- Johanna Ogden’s book, which was released in June, follows two movements for Indian independence with ties to Oregon.

In a country that boasts of “liberty and justice for all,” some Americans have few qualms about belittling and even demonizing people who look or sound different than they do, or who — heaven forbid — have arrived from a different part of the world with the dream of rebuilding their lives as new Americans.

A new book by Portland activist and independent historian Johanna Ogden shines a light on a specific immigrant population from a century ago and how its quest for belonging, right here in the Pacific Northwest, evolved into two different avenues of ambition.

“Punjabi Rebels of the Columbia River” investigates small West Coast populations of men who had come from India, and who typically were called “Hindoo” at the time, despite their various religious identities as Hindus, Sikhs or Muslims.

“Punjabi Rebels of the Columbia River” by Johanna Ogden

Oregon State University Press — 296 pp — $29.95

As far back as 1858, Queen Victoria had conferred British imperial membership on her Indian subjects, and after that, many Indian migrants sought work or education abroad to save family farms at home.

But when their migration to another member of the British Commonwealth, Canada, was spurned by a racist government there, the wave of Indian migrants turned southward toward the booming farming and resource-extraction economies up and down the West Coast of the United States.

Even in America’s much-vaunted land of the free, however, the migrants encountered both racism and violence at the local level, while the U.S. government scrambled to institute exclusionary immigration policies after the fact.

Bitterly awakened to their precarious standing throughout the world, the Indian diaspora became radicalized. In several mill towns along the Columbia River, Indian workers quietly began organizing to go back and “clean house” in their homeland by overthrowing British rule.

Significantly more tolerance was afforded to the Indians in Astoria, enough so that proponents of turning out the Raj and establishing Indian independence were able to crystallize their ambitions and openly announce the formation of the Ghadar Party, which went on to become an international political movement.

Author Ogden also relates the story of Bhagat Singh Thind, an Oregon-based Indian immigrant who sympathized with the Ghadar movement, but who chose to remain in America when many of his countrymen returned to India to fight for independence.

Thind chose a different battle for himself: a quest to earn full American citizenship. His efforts took him all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which issued a decision that not only denied him his dream, but dismantled the citizenship status of others and, Ogden writes, “enshrined whiteness as power.”

It wasn’t until 1936 that Thind was able to obtain American citizenship due to a loophole in the law relating to his service in the American military during World War I — two decades earlier.

In the epilogue to “Punjabi Rebels,” Ogden challenges readers to think about the continuing influences of our colonial legacy today … “judged by present-day United States or India … Where does either country stand in the lived reality of a promised multiethnic and just democracy?”

“Punjabi Rebels of the Columbia River” by Johanna Ogden

Oregon State University Press — 296 pp — $29.95