Memories of Bayocean

Published 9:00 am Monday, April 14, 2025

- Harold Bennett walks down Pacific Avenue near his home in Cape Meares. (Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

Susan Bagley Barr still remembers the winter morning in 1951 when a rogue wave swept through a gap in the dune ridge and onto the blue DeSoto her mother was driving along Bayocean Peninsula.

She was in the third grade, riding in the backseat with her older sister, Sally, wearing a favorite peach-colored dress with a white collar. The girls were headed to school in Tillamook, east of the narrow sand spit where the Bagleys had lived for the past six years, when the surge caused the car to stall.

“At that point, my mother grabbed us, and we grabbed our lunch boxes and ran for the Cape Meares side,” Barr said. “I don’t know what happened when we got over there. I do know that I dropped my lunch box, and that somebody found it on the ocean side a week later.”

The Bagley family’s blue DeSoto parked outside their home. (Susan Bagley Barr)

Trending

That morning foretold more of what was to come for families who lived on this part of the Oregon Coast. “It was scary,” she said. “It’s scary when you’re running from something that might take your life, and that was, I think, the beginning.”

Susan, Sally, and their mother, Elizabeth Bagley, spent the rest of the school year living in a one-bedroom Tillamook apartment. For months, they continued to visit Bayocean on weekends. Eventually, those visits would come to an end.

A promised land

In 1907, the 4-mile-long sand spit on the western edge of Tillamook Bay was just beginning to be developed as a grand, exclusive summer resort.

Thomas Irving Potter had convinced his father, Thomas Benton Potter, a developer who had found success in Portland, San Francisco and Kansas City, and in coastal towns like Half Moon Bay, California, to invest in the pristine shore. With the promise of a Pacific Railway & Navigation Co. line from Portland by railroad magnate Elmer Lytle, the Potters bought land from homesteaders and sold 1,000 lots within three months.

A view of the natatorium, which collapsed in 1932.

Bayocean Park was to have a 300-room hotel to rival the celebrated Hotel Del Monte of Monterey, designed by Portland architect John Wrenn on a 100-foot ridge overlooking both the bay and the Pacific. Beside it, a 60-room annex would house a full-time staff.

Trending

“Twelve acres of a naturally beautiful park have been set aside as the hotel grounds,” read one advertisement that ran in The Oregonian on Oct. 4, 1909. “This park extends toward the bay nearly to Bay Boulevard, the equivalent of Atlantic City’s Boardwalk.”

Only the annex was built. Harold Bennett remembers playing in its ruins as a child in the 1940s.

“When we moved in, it was just a concrete shell for the first floor,” Bennett, who moved with his parents to the spit from Sioux City, Iowa, at the age of 2 in 1942, said in an interview at his home in Cape Meares, “and then they had one or two wooden floors above that.”

Elizabeth Bagley stands at Jackson Gap after the Nov. 13, 1952, washout that turned Bayocean Spit into an island. (Susan Bagley Barr)

Barr remembered standing up on the cement foundation with her father, George Bagley Jr., and looking out at the horizon. “At that point, we were looking down to the ocean. And, of course, that’s before everything continued to erode and get flatter,” she said.

Before erosion started in the 1920s, Bayocean thrived. The town had paved streets, electric-lit sidewalks, a general store, two restaurants and a working pier. There was even a saltwater natatorium with a wave-generating machine, where Bagley Jr. and his brother, Bill, used to swim. In all, 59 cabins and other dwellings were built on the spit.

By 1960, all of it was gone.

Retracing steps

For Jerry Sutherland, hiking the brushy, salal-covered peninsula continues to fascinate. An independent historian and author of the recent book “Bayocean: Atlantis of Oregon,” he has spent years compiling maps that show how the landscape has shifted over time.

“You walk out there now, and it’s nothing like it was,” he said.

The moon rises over dune grasses on Bayocean Peninsula. (Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

The Pagoda Houses, now in Cape Meares, were some of the few structures to be moved off the spit. (Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

Sutherland once helped Barr locate a property where her grandparents stayed during early visits. George Bagley Sr., who was appointed circuit court judge for the judicial district that included Washington and Tillamook counties in 1915, eventually purchased several Bayocean lots.

Changes came slowly. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers at first recommended a dual-jetty system at the mouth of Tillamook Bay, but later reached a compromise. One jetty, on the north side, was completed in 1917.

The Corps had never before built only one jetty and hadn’t considered how it might affect the coastline.

“Once the North Jetty was built, that started the erosion,” Sutherland said. “Houses got moved back to avoid it because the lots were 100 feet (deep).” Yet even as some fell into the sea, others were going up. The last house on Bayocean Spit was built in 1950.

At that time, Barr was living in a house backed up to the bay.

“The living room went from the front of the house to the back of the house, and then there was the large window that looked out behind, and it had a fireplace, and we had the little doll bed in one corner that we played with,” she recalled, “but we were outside a lot, running around.”

Susan Bagley Barr, right, and her sister, Sally, pose in front of their dad’s crab boat, the Sally Sue. (Susan Bagley Barr)

She would wander down to the bay, sinking into the sand and, further, the mud flats neighborhood kids called “the big punches.” She rode a bicycle, picked strawberries and tended to a flock of banty chickens, who would sometimes follow the kids down to the beach.

Up in the forested hills, a group of friends nicknamed themselves “The Poison Berry Club” for the salmonberries they liked to pick — though salmonberries aren’t poisonous. “We used to go up on the hill, and you could look out on the ocean,” Barr said. “My mother had my dad’s whistle from the army, and she would call us back.”

“I didn’t realize that there were any problems,” she said.

Saying goodbye

Perry Reeder Jr. was about 6 years old when his family moved to Bayocean.

It was the summer of 1944. As with many who arrived on the spit during World War II, after the natatorium and other structures had collapsed, the Reeders were drawn by affordable housing and lucrative job prospects. Naval Air Station Tillamook had given a boost to the local economy, and the family was able to rent a cabin for $10 a month.

“It was like paradise growing up down there because there were a lot of other boys,” Reeder Jr. said. “We made lifelong friends with those families, and those boys are like brothers to me.”

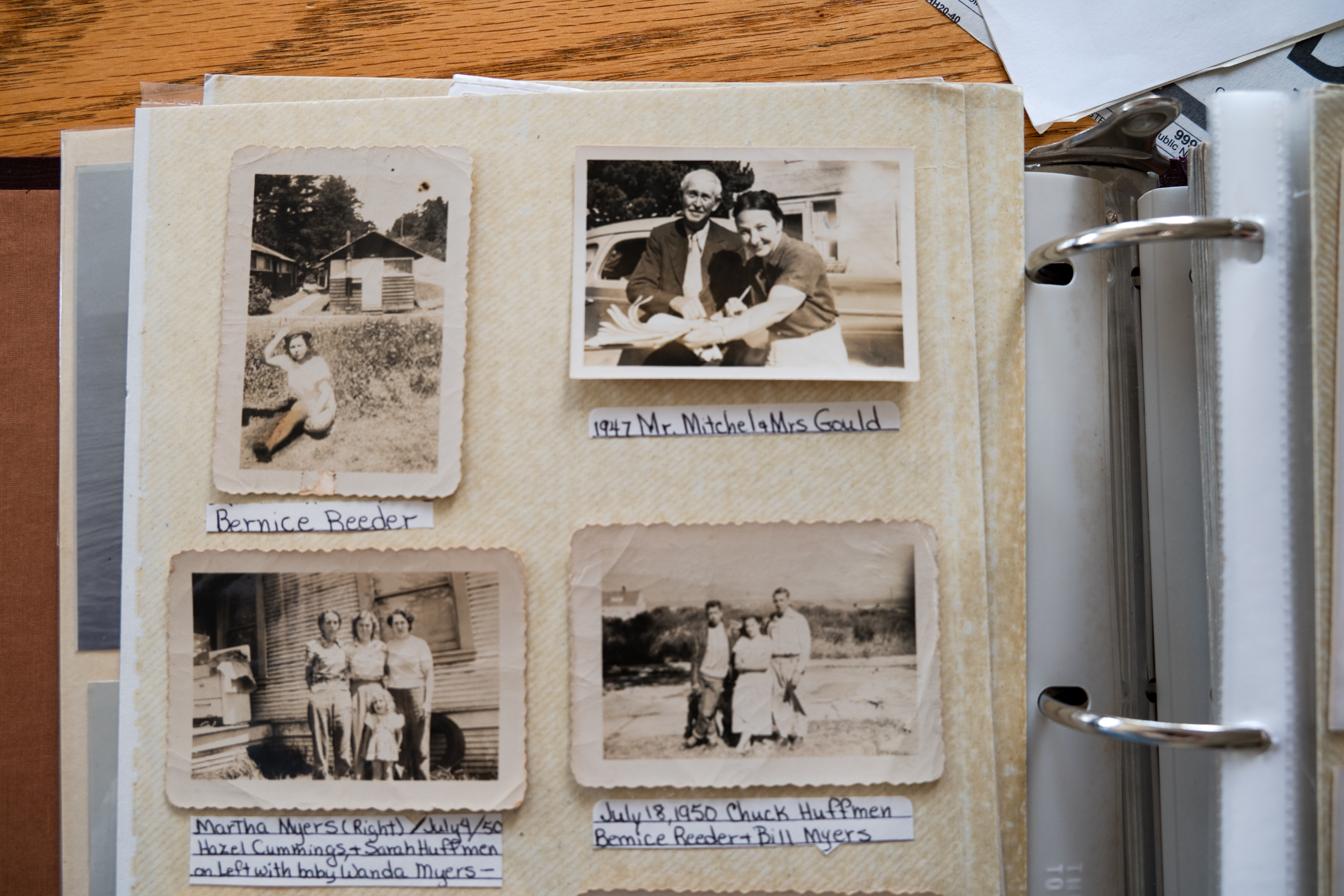

Photo albums of Perry Reeder Jr.’s at his home in Oceanside. (Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

As he flipped through a photo album at his home in Oceanside, a few miles south of Cape Meares, he pointed out friends and neighbors from years gone by. There were Francis and Ida Mitchell, owners of a local mercantile, and a group of boys who often went surf fishing together. He spoke of wartime blackouts, air raids and the U.S. Coast Guard Beach Patrol, war dogs who kept watch over the shoreline.

Like Barr, he has fond memories of what was once a sandy beach on the bay. “The northwest wind always comes up at 11 o’clock here on the coast, and it blows on the bay side,” he said.

Over the years, Reeder Jr. has attended reunions of Bayocean alumni, including those who were students at Bayocean Schoolhouse as children. The school closed in 1948. Bennett was a student, too. Back in Cape Meares, he pointed to the schoolhouse building, one of the few surviving structures to be moved off the spit, which is now a community center steps from his front door.

Walking down the street, he pointed to another, the Pagoda houses. “They were actually two houses that sat within a breezeway of each other, and my mother cleaned those houses,” he said. “I remember when they were moved because they took a tractor up there and made kind of a road, a sand road, and put them over there as one house.”

A lone chair looks out over the dunes on Bayocean Peninsula. (Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

After earlier breaches, a winter storm on Nov. 13, 1952, left a nearly mile-wide gap between Bayocean and the mainland, turning a peninsula into an island. Letters on a sign in the Mitchells’ storefront window were covered up so that instead of “Watch Bayocean Grow,” it read “Watch Bayocean Go.”

The Bagleys’ home was on stilts, ready to be moved, but didn’t make it.

“My dad went back with his brother to tear down the house and bring out the lumber so that we could rebuild in Cape Meares, where they purchased a lot,” she said. “Helen Reeder (Perry Reeder Jr.’s sister) and I went with him for the week, and at that point, we had a wonderful time because we got up and had too many pancakes for breakfast, and then we headed out and just had the ocean to ourselves, along with our dog, of course.”

That was the last time Barr would see Bayocean for many years.

“I remember it as a place to meet friends, explore, play games, walk the beach and look for agates,” she said. “It was a great place to be a kid. There were kids around. We had the ocean. We had the bay. We could ride our bikes up and down the cobblestone street and then meet again the next day.”

Further reading

“Bayocean: Atlantis of Oregon” by Jerry Sutherland, Beaver State Press, 2023

Also, follow Sutherland’s blog for stories and updates at www.bayocean.net

“Bayocean: Memories Beneath the Sand” by Perry Reeder Jr. and Sarah MacDonald, Xlibris, 2017