The Liberty Theatre at 100

Published 11:00 am Sunday, April 13, 2025

- The Liberty Theatre was built amid Astoria's recovery after much of the city was destroyed by fire in 1922. (Liberty Theatre)

You may already know the Liberty Theatre in downtown Astoria is an architectural gem, an elegantly restored theater and movie palace that harks back to its original splendor as a symbol of a resilient seaport town. The arc of the 100-year-old theater’s rise, decline and revival is by now a familiar one to Astorians.

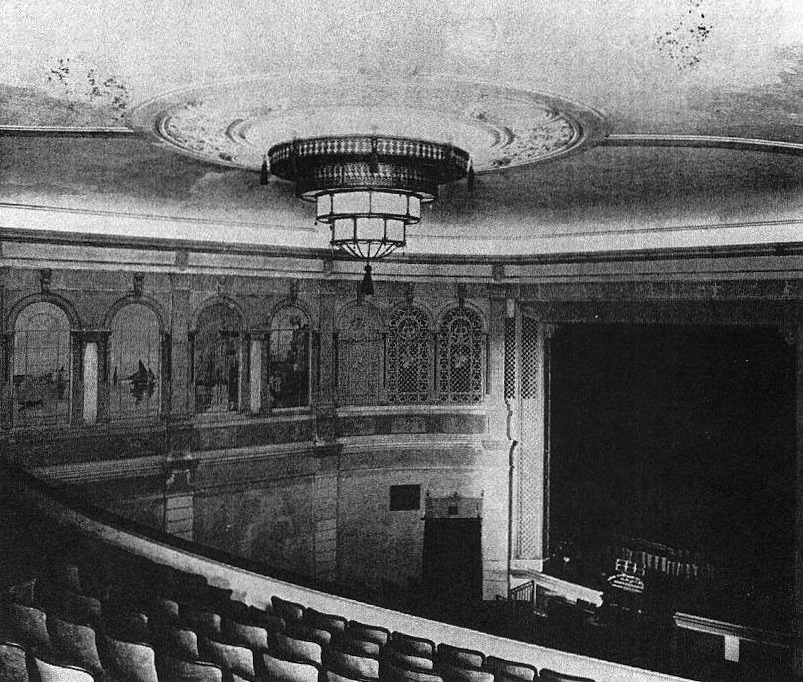

And yet, the stately kiosk, the beckoning marquee, the painted panels of Venetian canals and the ornate embellishments of the pilasters are only part of the reason locals prize the Liberty so highly. The other half involves the role the theater played — and continues to play — in the social and cultural life of Astoria and the lower Columbia region.

The theater was once a place where people went not to just be entertained, but to be seen.

Trending

To enter the Liberty was akin to taking a cruise to an exotic destination, where elegant performances and evocative architecture promised to transport audiences to someplace memorable. And for those who didn’t have tickets, it was absorbing to watch the parade.

During the late ’20s and early ’30s, it was thought to be fun to park on Commercial Street on Saturday evening and watch the strollers … The preferred parking spot was on the southwest corner of Commercial at 12th Street. From that vantage point you could also see who was going into the Liberty Theatre.

—Don A. Goodall, Cumtux, Spring 1982

In fact, the theater today touches more people than it ever has, from fans of big-name acts like Lyle Lovett to middle school students on field trips. Under the leadership of executive director Jennifer Crockett, the Liberty today is the leading performance and entertainment venue in the region, touching people who would otherwise never have come inside. The theater’s second heyday is surpassing its first.

Jennifer Crockett, executive director of the Liberty Theatre, poses for a portrait. (Lukas Prinos/The Astorian)

Trending

Yet the Liberty’s programming, like the building itself, has rebounded from its dismal middle years, when paltry audiences settled in the broken seats to watch a series of forgettable movies. But let’s start at the beginning.

The curtain rises

The Liberty’s origins lie in a smoking ruin.

The Dec. 8, 1922 fire that tore through Astoria’s downtown left smoldering heaps of charred timbers and tumbled bricks over a stretch of 32 prime commercial blocks. Gone were more than 200 shops, restaurants and service firms.

From this devastation, Astorians came together to rebuild the city in a remarkable show of resolve and resilience. Within a couple of years, rebuilt rows of commercial buildings had risen from the devastation to again serve the community and visitors from other places.

At the center of the rebuilt city, on the corner of Commercial and 12th streets, the Liberty became the most dramatic symbol of downtown Astoria’s rebirth. On the block that had been home to the Weinhard-Astoria, the city’s premier hotel, architects John Bennes and Harry Herzog designed an Italian Renaissance entertainment palace that became the town’s signature downtown building. As it happened, the theater opened just as the vaudeville era was about to be eclipsed by talking pictures. While live performances continued at least into the World War II era, the Liberty became a showcase for the fledgling art of cinema.

The chandelier remains a centerpiece of the theater, reminiscent of the 1920s. (Liberty Theatre)

In its prime years of the 1920s and 1930s, the theater was a social center of the lower Columbia region. Astoria was a lively port town, with ferries plying the Columbia River, canneries employing immigrants and local people, and Chryslers, Studebakers and Ford Model Ts angled along Commercial Street. After it opened in 1925, the Liberty was a place where the people who lived here encountered the people who were passing through.

“My mother left Astoria High School when she was 14 and got a job as an usher right here. And she also sold tickets. They were hard in those days … She said every time the night was over, and if the money didn’t add up to what the tickets were, it came out of your wages … There were so many foreign seamen coming in here, and they didn’t speak English and didn’t understand our money system, so they would always shortchange these poor sailors just in case the tickets didn’t add up at the end.”

— Karl Marlantes, speaking at the Liberty Theatre during the 2024 Creative Writing Festival

During the 1920s and 1930s, even during the Great Depression, people found reasons beyond movies to come to the Liberty. The Clatsop County Historical Society archives are full of references to the goings-on.

“The Elks Lodge Chapter 180 entertains 1,100 children at the Liberty Theatre Christmas party. (1932)” …“Hortense Stacey wins a trip to Hollywood in Liberty Theatre beauty contest (1927), “Lennart ‘Johnny’ Ross, 17, wins new Chevrolet in Liberty Theatre drawing. (1932)”… “Jack Dempsey, the huge-shouldered killer of the ring and the most colorful world’s heavyweight fight champion in boxing history, will appear on the stage of the Liberty Theatre tonight in a special bond show that opens at 8:30 o’clock. (1944)”

Astoria city historian John Goodenberger has written evocatively of those days, noting the appealing efficiency of the usherettes, the commanding presence of a Wurlitzer organ raised from the orchestra pit, and the parade of memorable onstage attractions, from tap dancers to explorer Roald Amundsen.

But in relatively short order the organ was sold, the proscenium arch hidden behind a movie screen and the lobby and auditorium apparently repainted with little consideration for the ornate flourishes that had distinguished the theater when it opened.

Within a few decades, the Liberty had become a tarnished gem, a neglected, chilly place where moviegoers shivered in their seats while watching the projected images of Doris Day, Elvis Presley, Ernest Borgnine and others. Astorians who went to movies in that era describe the experience as “yucky and spooky,” but there was little else to do downtown. The district around the theater had become a place where drifters could buy drugs and visit strip bars. The Liberty had become little more than a shell of the building that had been Astoria’s showpiece.

This 1946 photo shows the uniforms and smiles of ushers outside the venue. (Liberty Theatre)

The Liberty’s owner at the time, a Los Angeles lawyer named Edward Eng, “didn’t give a rip,” Goodenberger said. Eng spent no time in Astoria and seemed to care only about maintaining the tax break that came with owning a historic building.

Worse, Eng had hired contractors to carve two tiny cinemas into the balcony, flanking the main projection booth. The Liberty was able to show three films at a time, but the experience for audiences was anything but enriching. Preservationists did what they could to minimize the harm done by the remodeling and, fortunately, were able to protect the panels of Venetian scenes and for the decorative plaster walls.

With the building deteriorating and the moviegoing experience degraded, Astoria lost some of the glue that helped the town cohere. The unheated theater, with its sticky floors and broken seats, no longer was it a place where moviegoers were proud to be seen. It became a place to be avoided.

A second act

The Liberty’s second rebirth can be traced to the late 1990s, when a team of concerned Astorians led by Steve Forrester, then-publisher of The Daily Astorian, began working to rescue the building from neglect and further damage. Forrester said he was initially motivated to create and upgrade a space available to Portland performers but began to focus on the Liberty along with like-minded citizens, including Hal Snow.

Cannery Pier Hotel developer Robert “Jake” Jacob eventually pried the building from Eng after state historic preservation officials rescinded his historic building tax exemption. Jacob turned it over to the newly formed Liberty Restoration Inc., a nonprofit group, for $1.3 million raised through a city urban renewal grant.

To hear Forrester talk about the lengthy effort today is to recall the names of people and institutions in Astoria, Portland and elsewhere who came to the Liberty’s rescue: Snow, Jacob, Goodenberger, the Oregon Community Foundation, Edith and Bill Henningsgaard, Jared Rickenbach, Michelle Dieffenbach, Michael Foster, Jim Flint, Paul Benoit, Cheri Folk, Skip Stanaway, Marge and Theodore Bloomfield, Betty Smith, Norm Yeon, Judith Ramaley, Daniel Bernstine, Willis Van Dusen and others.

Scot Thompson attends to repairs above the theater’s front awning ahead of its 100th anniversary in 2025. (Lukas Prinos/The Astorian)

Collectively, they soldiered through a broad and inspired effort that captured national attention, while focusing community energy on the Liberty. “It was like a political campaign,” Forrester said, the way a group of advocates worked to persuade donors and investors that saving the Liberty was worthwhile. After years of effort, they achieved broad buy-in from many Astorians and others in the lower Columbia region. In that sense, the restoration effort was an echo of the burst of civic determination that rebuilt downtown in the wake of the 1922 fire.

“I was immensely proud,” Forrester said, who added a caveat: “It’s one thing to restore a theater and finish. It’s another thing to operate it.”

And that’s where Crockett has taken over. Hired as the renovated Liberty’s third executive director, she has overseen an explosive growth in programming, quadrupling the number of shows hosted by the theater and touching the community in ways that even the old Liberty never did.

“We’re using and engaging every corner of the theater,” she said on a recent day when, as it happened, the Kids Make Theatre program was one year old.

The youth theater school, funded by earmarked gifts, offers theatrical experience, from acting to prop-making, to kids of all ages. “We have 400 kids passing through every week,” Crockett said. “It’s bonkers.”

Crockett has worked to connect the Liberty with schools, noted longtime backers Dan and Sue Stein, of Astoria. They cited the intimate performances that take place in the second-floor McTavish Ballroom, the Cinco de Mayo performances that brought new people into the theater, the outreach to high schools and the memorable showing(s) of “Elf,” the Will Ferrell Christmas movie, when audience embers threw socks toward the screen to mimic a snowball fight.

“Her energy and joy really opened the Liberty to everybody,” Sue Stein said. “It’s a very welcoming environment.”

In introducing singer Storm Large to a sold-out audience last year, Crockett talked about how the Liberty was once considered a place geared only to upper-crust audiences. But now it hosts everything from dog shows to stand-up comics, aiming to attract people who might otherwise have stayed away.

“We’ll try anything once,” she said.

Backers have responded. Last year’s capital campaign raised money mostly to repair a leaking roof, and supporters pushed it over the top at a gala auction and paddle raise.

In its 100th year, the Liberty is perhaps in better shape than it ever has been, but the job of maintaining and enhancing it will never be finished. Crockett speaks hopefully of potential tangible improvements, such as a fly loft that would permit performers to ascend and fly above the stage, as well as about improvements to the theater’s balance sheet. The Liberty, she said, needs a permanent endowment to help carry the theater into its second century. You’ll hear more about that soon.

OK, that’s enough talking. The show is about to start.