Butterflies of the Columbia Coast

Published 11:00 am Friday, April 11, 2025

- The Oregon silverspot butterfly persists in only a few spots along the Oregon Coast. It was recently reintroduced to Saddle Mountain. (Illustration by Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

Let it be said from the outset that we privileged ones who dwell near the mouth of the Columbia River, on either side and for some distance inland, do not occupy butterfly nirvana. If you have been under the impression that the rainforests of the world are populated by scads of beauteous butterflies, then revise your view slightly: this is true of tropical rainforests — but not temperate rainforests.

Butterflies tend to do very well, in both abundance and diversity, under conditions that are hot and wet (the tropics), hot and dry (the desert) and cold and dry (the Arctic). Cool and wet, not so much. And those are the conditions that prevail here, in our beloved temperate rainforest.

The persistent rain and heavy forest cover tend to discourage these sun-loving insects, whose immature stages are likely to rot in the wintertime. Our diversity is better expressed in ferns, mosses, mushrooms, conifers and other organisms that thrive under cool, shaded, moist conditions, or else migrate. So the butterflies here are subtle, compared to elsewhere.

That said, a modest array of species from across the spectrum of butterfly families has adapted well to the plants and climate of the lower Columbia, and they do very well here. Happily, many of these are both beautiful and fascinating, and may be found with moderate searching and attention to the landscape. So we are not at a loss for butterflies here, even if there are far fewer than we might find in the Cascades, Olympics, or Willamette Valley and points south to the Siskiyou and beyond.

Here I will acquaint you with a number of butterflies that you might well encounter here along Our Coast and its adjacent inland areas, and give some tips as to how you might go about spotting them. Since butterflies have different life histories and particular emergence times, it might be best to do this by running through the butterfly year along the Columbia Coast.

In the spring, look for the mourning cloak, green comma, Clodius parnassian and California tortoiseshell. (Illustration by Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

As winter turns toward spring, with hazel catkins bursting and pussy willows not far behind, the very first butterflies of the year are posed to emerge — not from their chrysalis, but from a hollow tree, shed or other shelter. Eight Northwest butterflies overwinter as adults, and may be seen on the wing even in January or February, or certainly in March, when the sun is allowed to shine enough to warm the air and bring out these hibernators. Around here, the most likely ones to see are mourning cloaks, California tortoiseshells, satyr anglewings and green commas. Watch for these sizable, often rusty-colored butterflies taking their hungry sustenance at sapsucker holes or pussy willows. They may look tatty after their long winter in-dwelling, but their bright offspring will appear again in the fall.

Usually the first fresh emerger to pop out of its pupa is the echo azure, related to the eastern spring azure, which Robert Frost described as “sky-flakes/down in flurry on flurry.” Members of the gossamer-winged family, the blues, coppers and hairstreaks, azures are a lovely lilac-blue on the upper side, silvery white below. Their caterpillars feed on flower buds of many kinds of shrubs, especially osier dogwood, ocean spray and ninebark around here. The adults visit early flowers such as sweet coltsfoot, and the males collect on sandy riverbanks and muddy logging roads to sip salts from the soil. So when you spy bright blue fliers on early spring days, your eyes are not playing tricks on you.

These increasingly rare warm and sunny spring days may also reveal relatives of the azures called elfins. The tiny, chestnut-and-mauve brown elfin haunts kinnikinnick and salal in seaside woods, while the (actually pine-feeding) pine elfin patrols shore pines among beach dunes at Leadbetter Point and Fort Stevens, and the bramble green elfin seeks out rosy lotus flowers higher in the Oregon Coast Range. All of these are thumbnail-sized, as is our earliest skipper — the buzzy gray two-banded checkered skipper, which lays its eggs on flowers of big-flowered geum and trailing blackberry in woodland glades and roadsides.

In April, the forest and rural roads begin to be spattered by lots of margined whites floating along like bits of tissue paper. These nearly pure-white butterflies with darker veins beneath favor the flowers of ladies’ smocks (Dentaria or Cardamine) on which to lay their eggs, like most of the whites requiring hosts in the mustard family.

They are native to our temperate rainforest and very well adapted to it, doing well in clearings among both old-growth and managed forests, if not sprayed. But when you leave the wilder places for the towns and gardens, the species of white shifts from margined to European cabbage white. This familiar butterfly, introduced into Quebec in 1861, covered the whole continent extremely successfully, feeding as larvae on cabbages, broccoli and other crucifers. It is by far the commonest species in Astoria, flying from spring through fall in successive generations. I love it, as it is often the only butterfly to be seen on a sunny day in town or farmland.

The late spring brings some real warmth, and with it the tide of swallowtails. The first to mention is another white butterfly, but bigger and floppier than the actual whites. This is the Clodius parnassian. Though classed as a swallowtail by morphology and DNA, it looks nothing like the others. It is a biggish, rounded butterfly of waxen white with sharp inky-black and cherry-red spots. Its caterpillars feed on wild bleeding heart, so you can spot it floating along many a woodside road or path all summer long.

Usually by May Day or so, the more obvious true swallowtails will be out too. We are graced with three species here: the pale tiger swallowtail, first out, often in time to nectar on your lilac bushes. It is quite whitish too, banded in thick, black tiger-stripes. A week or two later come the western tigers, lemon-yellow with narrower black tiger-stripes. Both of these feed on broad-leaved trees like willows, cherries, red alder and cascara, and can be truly abundant when conditions are right, even in the city. (Many people call them monarchs, which do not occur here because of the absence of milkweed.)

Our final species of the family, the anise swallowtail, has two distinct broods, in spring and late summer to fall. It sports yellow bands across black wings and it lays its eggs on seaside angelica, cow parsnip, dill, parsley and other members of the carrot family. Look for them on lilacs in the spring and butterfly bushes in August, and along headlands, breeding almost down to tidewater at Leadbetter Point.

As spring goes on, watch for western meadow fritillaries in the forest clearings. Like all fritillaries, they feed on violets. When they fly, their brilliant orange, black-dotted wings, and their violet-and-rust undersides when at rest, leave little question of their identity. Another softer orange small one — actually Dreamsicle-colored — may be seen haunting the back-beach grasses on the Oregon side about this time. Known as the ochre ringlet, it is often seen tucked up under spiderwebs beneath Queen Anne’s lace along seaside dunes. The related large wood nymph may be spotted flip-flopping through pasturelands and wood-edges some distance inland from the shore. The males are dark chocolate and the females cocoa, each with conspicuous eye spots on the wings to draw birds’ attention away from their bodies. Both ringlets and wood nymphs feed on grasses as green, camouflaged caterpillars.

Warm and sunny spring days may reveal elfins, brown, green and pine-feeding. (Illustration by Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

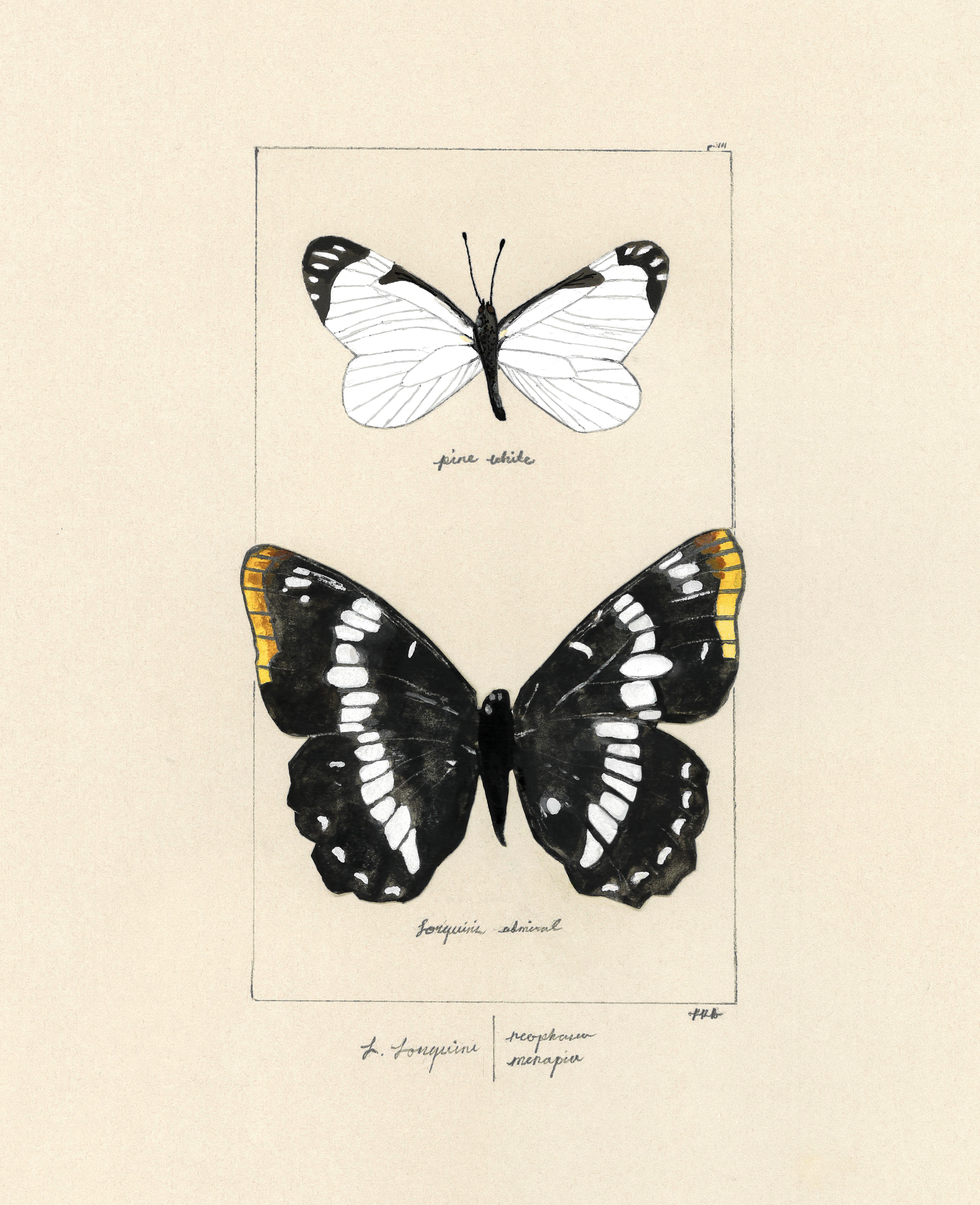

Summertime sees the flights of several colorful members of the brush-footed family. A common resident of towns, countryside and anywhere with willows and ocean spray, the very handsome Lorquin’s admiral soars back and forth between occasional flaps. Flying out from a chosen branch, males patrol particular territories where they are most likely to encounter females. Jet-black with broad white bands and cinnamon wing tips, they are unmistakable and unforgettable.

Another butterfly commonly called an admiral, the red admiral (or red admirable), is not closely related. It too is black, but its wing bands are scarlet or fire-engine orange, not white. Look closely and you will see its resemblance to the several species of ladies — painted lady, West Coast lady and American lady, each with salmon or citrus-orange wings with distinctive black, tan and white variegations. All three species fly into our area in the summer from farther south, so their numbers are highly irregular and their appearance unpredictable year to year. They especially love to nectar on zinnias and butterfly bushes.

A much smaller brush-foot appears sparsely in spring but much more abundantly in its summer generation. This is the bright orange-and-black spackled mylitta crescent. A mother-of-pearl crescent spot at the outer edge of the underside of the hindwing gives its group the name “crescents.”

The brighter orange males, just an inch across, glide and flap, glide and flap, close to the ground, patrolling roadsides, edges of rutted tracks or fields and country lanes, all through late summer into fall. The slightly bigger females are a duller orange. They spend their time visiting flowers and seeking their host plants to lay eggs. They feed exclusively on thistles — native or introduced. So if you do not have a compelling reason to eliminate thistles, by all means, keep them around, because they are also the caterpillar host for painted ladies and a favorite nectar source of swallowtails, fritillaries and others.

Another tiny flier of summer is the purplish copper. You will find it in damp spots or waste areas in fields where pink knotweed or smartweed grows (not the big Japanese knotweed). Females are orange- and black-spotted, while the males are tarnished-penny brown with an extraordinary purple sheen when seen in the right light. They occur through much of our area, though seldom commonly unless you come upon a good big knotweed patch.

One other, very special species of copper can be claimed by the Columbia Coast, but it is very rare and few have seen it. A newly described subspecies of the mariposa copper (more common in the Cascades), it is known as June’s copper. Found at Ilwaco in 1918 and never since on the Long Beach Peninsula, it was discovered among the Gearhart Fen Complex in recent years by local naturalist Mike Patterson. Efforts to find more and to protect their fen-cranberry bog habitats are underway. The uncommon, sedge-feeding dun skipper may be spotted here as well.

Which brings us to late summer, and the most famous of our Columbia Coast butterflies, the Oregon silverspot. This silver-dollar sized, silver-spotted brush-foot was first found near Ocean Park in the nineteen-teens by early lepidopterist Agnes Veazey. After many years of its anonymity, I found it again near Lake Loomis in 1975. The butterflies’ federal listing as a threatened species was one of the Portland-based Xerces Society’s first campaigns, nearly 50 years ago.

Since then, despite lots of monitoring and habitat conservation efforts, it has dropped out of Washington and persists only in a few Oregon coastal remnants of the old, native-fire-dependent salt-spray meadows and Mount Hebo. Recently, it was introduced to Saddle Mountain, and the hope is to reintroduce it to restored Washington habitats in coming years. One colony, at Cascade Head Preserve north of Lincoln City, survived thanks to the nectar of the despised exotic weed tansy ragwort, until native nectar sources were reestablished.

The pine white surfaces in late summer as the Lorquin’s admiral, common in towns and the countryside, hangs on. (Illustration by Lissa Brewer/The Astorian)

Shifting now from rare to common species, there is no more widespread or successful butterfly along the Columbia Coast (and indeed throughout the region) than the woodland skipper. There are many species of grass-feeding little skippers of tawny coloration and rapid flight, but most of them fly in spring and in specialized habitats outside our purview. This one emerges in late summer, in almost every open, sunny habitat available. Many people know them in their gardens, zipping around among herbs, asters and many other flowers. They seem like familiar neighbors or garden sprites. Their orangey-gold wings marked with black dashes are short and triangular, and their bodies thick with powerful flight muscles. Try to get a peek at their confiding and, frankly, cute faces, with their big eyes, short antennae and furry palpi. They thrive on many kinds of grasses, native and nonnative, so long as they are not cut too short and never, ever sprayed. Woodland skippers, prolific everywhere but deep woodland, are on the wing from Aug. 1 to Oct 1.

As summer wanes, two members of the whites and sulphurs family may appear, one of each. First, only among the shore pines at the beach, seek out the ghostly, lovely pine white. You may see them floating about the tops of the pines or Douglas firs, whose needles their exquisitely cryptic larvae consume; or they may come down to nectar on the flowers of hawkbit, late-blooming wild strawberry or garden lobelias, among others, especially in the mornings and later afternoons. The males are milky white with crisp and narrow black veins and black-chained tips. The females are more lineny, with smudgy black veins, and very striking crimson markings below. How lucky we are to have two of the few pine-feeding butterflies right here, both very beautiful — the western pine elfins in spring, and the pine whites in late summer into early autumn. Head out the piney strip behind the sea and dunes, and try to see them both.

Meanwhile, the orange sulphur (or alfalfa butterfly) shows up from the east side and the Cascades some summers — just a few, or in certain years, hundreds or thousands, laying their eggs on red clover for one final generation. They last as long as the weather permits — I saw one big female here in Gray’s River on Thanksgiving one year — and then die back until next year’s recruitment. Seek them in hayfields and pastures, and be prepared for shocking oranges.

Finally, the last warm days of autumn see the fresh new tortoiseshells and anglewings flitting about in search of late nectar or rotting fruit to tank up on prior to their long winter hibernations. The bright satyr anglewings will be seen especially near nettle patches. In fact, three of our loveliest common butterflies depend entirely upon stinging nettles for their caterpillars’ development: the satyr anglewing, the red admiral and Milbert’s tortoiseshell.

Nettles are the sine qua non for these spectacular residents. The caterpillars of California tortoiseshells, however, feed on buckthorns, mountain balm and mountain lilacs in the Cascades. Adults move down into western counties in late summer, having defoliated their hosts. Sometimes they breed here on ornamental Ceanothus or maybe Cascara, and some years they build to such numbers that Patterson has seen them migrating south along the seawalls and shorelines. It is not uncommon, but always delightful, to find one overwintering in one’s woodshed or cellar. But the finest sight of autumn butterflying might be to witness a bright, fresh mourning cloak basking or nectaring on mums or asters before turning in for the winter — all dark chocolate, French vanilla and blueberries, a butterfly for the ages, wherever you see it.

I hope this little excursion through the year with our local butterflies might encourage readers to seek out this rainbow resource for themselves. In order to optimize your butterfly-spotting opportunities, follow these simple rules: visit open, flowery, sunny places with your eyes wide open. Grow all the food and nectar plants you can in your garden or spare land or flowerbox for butterflies and other pollinators. Make sure the plants you buy have not been pretreated with neonicotinoid pesticides, and never, ever spray these or other butterfly-toxic products yourself. Happy butterflying!

To find ways to help with butterfly and pollinator conservation, visit www.xerces.com. And to identify and get to know all of the butterflies of our Columbia Coast and surrounding regions, pick up a copy of the Timber Press book, “Butterflies of the Pacific Northwest” by Robert Michael Pyle and Caitlin C. LaBar from one of our local booksellers.