Gyotaku fish printing with Duncan Berry

Published 9:00 am Monday, February 17, 2025

- A gyotaku octopus print made in a workshop at RiverSea Gallery in Astoria.

The octopus was a little thing, no bigger than the palm of my hand, as it lay on a table over a sheet of brown paper at RiverSea Gallery in Astoria.

A woman leaned in with a pair of tweezers, positioning it just so as if to perform some sort of surgery. But the creature wasn’t moving.

She rolled on the first coat of ink, then the second. Blue-gray, then cyan, before a thin sheet that would soak in the pigment. Duncan Berry, the artist behind the table, leading a workshop at the opening of his solo show “Icons of the Sea,” instructed her to count to eight. One, two, three, count each of the tentacles as she gently pressed on the paper and let the ink through.

Trending

The method is called gyotaku, from “gyo,” meaning fish, and “taku,” meaning “impression.” It’s a traditional Japanese form of printing fish, dating back to the 19th century, and the chosen medium of Berry, who lives and works from a studio at the Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve on the central Oregon Coast.

Berry’s process, which also draws on Western traditions of botanical and nature printing, captures direct impressions of life on land and in the sea, “nature as a printing press,” as he described it.

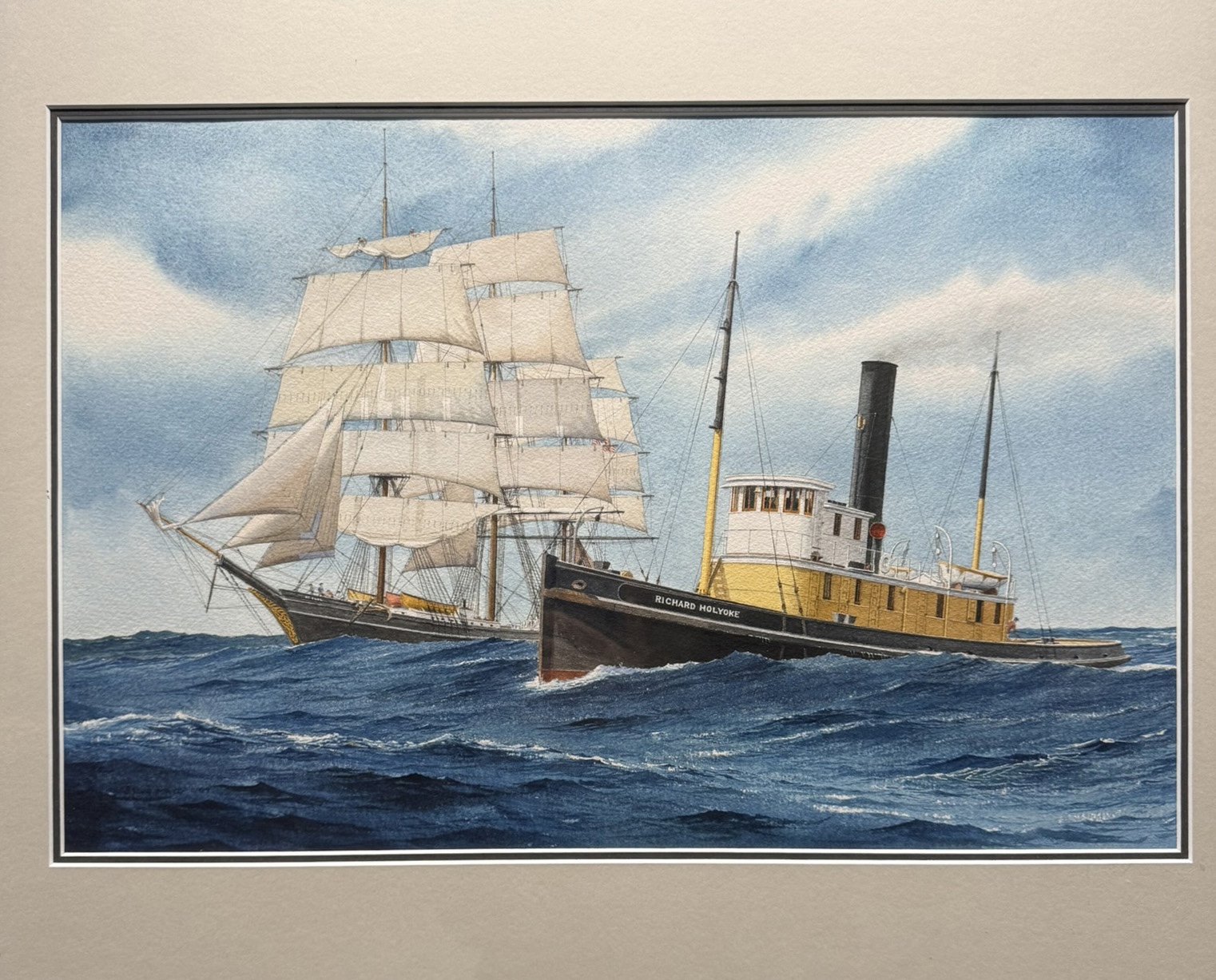

Several of his pieces are also in a RiverSea group exhibit, “Netted,” on display with the solo show through March 4. One, of an albacore tuna swimming with herring, is featured as poster art for the 2025 FisherPoets Gathering and appears on the cover of this week’s issue.

After observing a few others, my turn came to make a print with the octopus. Keeping its tentacles distinct, I tried guiding them one way, like branches of an old, windswept cypress tree. Drifting, I thought, still and quiet in the deep blue sea.