Bookmonger: A good pick for Black History Month

Published 9:00 am Monday, February 10, 2025

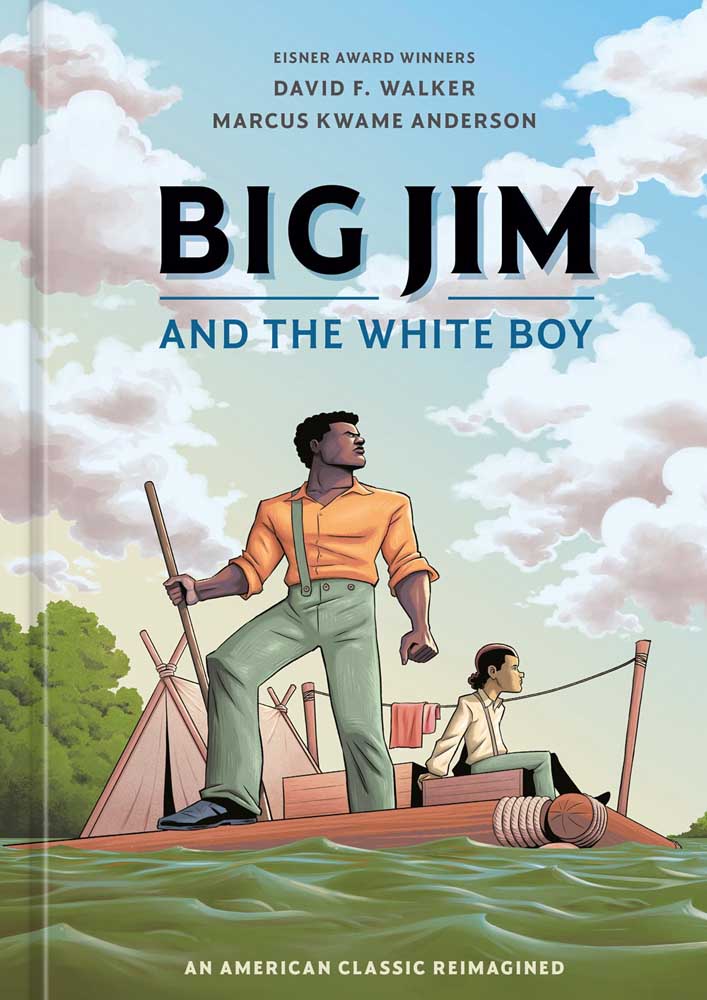

- “Big Jim and the White Boy” revisits Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” through the eyes of Jim, an enslaved Black man who is one of the book’s main characters.

It takes more than commemorative months to celebrate any of the various, complex cultures that imbue American society with the verve and diversity we’re noted for, but in honor of Black History Month, a look at a hefty graphic novel that came out last autumn.

David F. Walker is an award-winning comic book author, journalist, filmmaker and part-time instructor at Portland State University, who teamed up with illustrator Marcus Kwame Anderson to reconceptualize an American literary classic: Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

“Big Jim and the White Boy” is set up as a conversation or argument between two old codgers — none other than the characters of Jim and Huck themselves. They are sitting on a porch, surrounded by Jim’s descendants, and sharing their memories from 80 years earlier, when they floated on a raft down the Mississippi River in 1855.

This week’s book

“Big Jim and the White Boy” by David F. Walker and Marcus Kwame Anderson

Ten Speed Graphics — 288 pp — $35

But Walker flips the script in this expansive update of Twain’s book, revisiting the plot points of the original story but telling things from Jim’s perspective. And it’s clear that the character, a formerly enslaved Black runaway, has serious problems with the way Twain told the story.

In the first place, Jim doesn’t like the “gibberish” dialogue that Twain gave him to speak.

“Every damn word comin’ outta that damn fool’s mouth in that damn book has me soundin’ like a special kind of ignorant,” Jim complains about the character he plays in Twain’s novel.

Even though Twain wrote the story nearly 20 years after the Civil War ended, he frequently resorted to limited, slavery-era stereotypes to draw Jim’s character.

Through Walker’s writing in “Big Jim” and Anderson’s multifaceted illustrations, a more dimensional version of Jim emerges, and a deeper awareness of what it must have been like to move through mid-19th century America as a Black man.

To provide context, the author mentions little-known but real Black heroes of that era.

Frank McWorter, for instance, was an enslaved Black man who, a quarter-century before the Civil War, purchased the freedom of 13 members of his family and himself — then founded an integrated town in Illinois.

Another example: the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment, comprised of both free men and runaway slaves, proved to President Lincoln the fighting mettle of Black soldiers when the Regiment confronted and vanquished Confederate forces twice their number in Missouri.

Repeatedly, this book’s readers will face questions about the laziness of bigotry, the ethics of violence and how the tenets of lost cause revisionism shaped perceptions of the Confederacy and upheld racist viewpoints for generations after the Civil War — including in Twain’s work.

But in spanning this story across generations, Walker helps us ponder how attitudes around race and status eventually do change.

“Big Jim” is thought-provoking, beautifully illustrated and a real page-turner. Sit down with it — during Black History Month or any other time.