Bookmonger: Forest stewardship as everyday practice

Published 9:00 am Tuesday, April 30, 2024

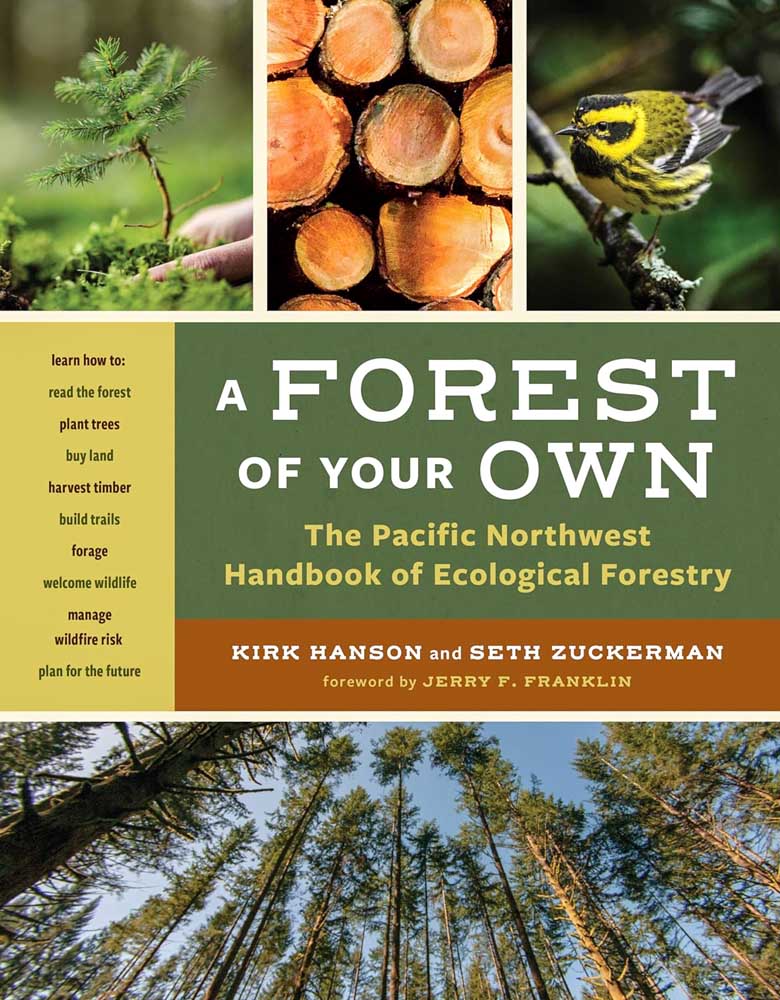

- Residents have a stake in the forests that local, state and federal governments manage. In “A Forest of Your Own,” authors Kirk Hanson and Seth Zuckerman share forest stewardship practices that can benefit even city residents.

”Looking after a forest is a practice, and it’s important to do it well,” writes Seth Zuckerman, one-half of the duo who has authored “A Forest of Your Own.”

Trending

With Kirk Hanson, a colleague at the nonprofit organization Northwest Natural Resource Group, Zuckerman has produced this informative guide on best practices for forest stewardship in the Pacific Northwest.

“We don’t expect every reader of this book to have their own forest,” Zuckerman writes. “We use the phrase your forest in this book to mean whatever forest you have in mind or is near to your heart.”

“A Forest of Your Own” by Kirk Hanson and Seth Zuckerman

Trending

Skipstone — 288 pp — $34.95

Whether or not you own a treed property, he points out, all Northwesterners have a stake in the forestlands that local, state and federal governments manage on our behalf. With more knowledge, even city folk can be better-informed advocates for healthy forest policies.

Co-author Hanson is a hands-on practitioner of ecological forestry. His family stewards 200 acres of forestland over three different parcels in western Washington — two near Chehalis and a third in the shadow of Mt. Rainier.

With boots-on-the-ground experience, he writes enthusiastically about lessons learned. Three generations of his family have worked on land they acquired that, in some cases, already had been logged over twice.

The Hansons remove invasive plant species and — taking climate change into account — replant with trees and undergrowth that should thrive and eventually transform into old-growth forests once again.

The family’s long-term plan includes selective logging to supply high-quality timber as a supplemental — not primary — income source while continuing to protect the crucial environmental benefits of carbon sequestration, habitat and biodiversity.

For readers interested in pursuing a similar endeavor, the authors advise how to “shop” for a forest. They share best-practice approaches regarding roads, watersheds and inventorying. They also discuss how to develop a comprehensive forest management plan, or even a conservation activity plan, that could qualify for federal funding.

As the name of their nonprofit organization implies, forests are a natural resource, from filtering water to sheltering myriad life forms to storing carbon.

Oregon forests, Zuckerman notes, “contain more than one hundred times as much carbon as the state emits every year through the combustion of fossil fuels.” And forests potentially provide one of the most environmentally sound construction materials — provided the timber is harvested thoughtfully.

While most forest industry giants have engaged in a century or more of “rapacious liquidation,” followed by the only marginally better system of planting monocrops, the authors point out that nonindustrial private forest owners currently control over a third of forestlands in Oregon forestlands and more than 40% of Washington state forestlands.

If thoughtful stewardship were to be practiced on those lands alone, imagine what improvements could be made in terms of insect infestations, disease control and wildfire management.

“Diversity is the key to healthy communities,” Hanson said about careful forest management. With plentiful photographs and lively writing, “A Forest of Your Own” provides bountiful advice and inspiration.