Astoria’s Pier 39 is among the last of its kind

Published 1:00 pm Wednesday, March 27, 2024

- Visitors to Pier 39’s Coffee Girl wave to the crew aboard the Arrow No. 2 as it dashes off on a river tour from its dock beneath the former cannery. (David Plechl)

Pier 39 shouldn’t even exist. Almost every other building like it — and many once lined Astoria’s waterfront — has collapsed, caught fire or otherwise crumbled.

At a quarter to eight on a clear Sunday morning, it’s cool near the water. The distant barking of sea lions echoes through the labyrinthine structures that make up the pier.

The wide waters of the Columbia River lazily loll beneath and around the old cannery building. Some parts of the building are nearly 150 years old.

A few early risers stagger slowly across the pier, lurching toward their first cup of coffee. The scent of freshly baked scones wafts beneath a still-locked door of Coffee Girl, a cafe with sweeping views of the river.

The pier at this hour is still largely empty of human occupants, but that will change. For now, a few cormorants drift through the water — deep blue and purple in the light of the early sun. A heron takes flight from a shoreline boulder, only to land a moment later atop an old wooden pile — the remnant of a train trestle that once connected the bustling Hanthorn Cannery to the rest of the country.

Once home to the Columbia River Packers Association, and later Bumble Bee Tuna, Pier 39 endures as a symbol of Astoria’s canning and seafood industries. (David Plechl)

Aside from a small structure or two and the decommissioned trestle, the old cannery and cold storage depot look much as they did when operations were in full swing. The clanking machinery, army of white-clad filleters and vast freezers stuffed with tuna are now gone, but there is new life in the old building.

When the door finally swings open to Coffee Girl, the line that had formed pours itself inward. The sounds of grinding coffee and hushed voices fill the space. Ships at anchor appear like decorations framed through the old mullioned windows. The mood is vibrant yet calm, much like the river in the morning.

The pier is just a trolley ride from Astoria’s downtown, but a world unto itself.

In truth, there are precious few places where you could have your torn sail repaired, grab a latte, stock up on scuba gear, gawk at sea lions, scarf a burger, down a pint, monitor the shipping lane, adopt a live crab, get a lesson in history and go home with a haircut. All in a day, or even a few hours.

Relishing in a challenge

Betsy Wentworth is the owner and operator of Coffee Girl. In the 1970s, she worked downtown at J.C. Penney, where she remembers the women from the plant coming in to shop after their long shifts filleting salmon, and how they “reeked of fish.”

She laughed, recalling that “no one seemed startled” by the fish odor.

Steps from where the original lunch counter served cannery workers for over a century, Coffee Girl is in many ways the living room of the pier, where even U.S. Coast Guard boats feel welcome to pull up for a quick cup of joe.

A historic photo of cannery workers is framed in a window at Pier 39. Inside, former workers’ names, notes and signatures adorn a vast wall, and relics can be explored in the pier’s Hanthorn Cannery Museum. (David Plechl)

Wentworth purchased the shop from its owner and founder, Zetty McKay, almost a decade ago. Little has changed, or needed to. The food and the coffee are still warm, fresh and familiar.

And, with panoramic views and access to the river, it’s a place to pause. “You can go out there and just sit and watch the sea lions,” Wentworth said.

She praised building owner Floyd Holcom for continuously fighting against the ravages of wind, rain and time that take their daily toll on the old structures.

“It’s the passion he has to keep this alive,” Wentworth said. “It’s just so much work.”

On this day, Holcom was nowhere to be seen. A former U.S. Army special operations officer, president and chief operating officer of the Salvage Chief and expert diver, his personal story is about as improbable as an old wooden cannery built above a tempestuous river surviving well into the 21st century.

One person thought he was on a dive. Another suggested he was training special forces. Maybe he was on a dive training special forces, opined yet another.

None of it would be out of the question. Long retired from the military, Holcom still supports the work of the special forces through dive training and as president of Pacific Defense Supply, a veteran-owned logistics group that provides equipment to federal and state agencies.

Holcom bought the pier and historic Hanthorn Cannery in 2002, and it’s been a labor love ever since. Not long after buying the property, he opened Astoria Scuba and Adventure Sports, the result of a lifelong passion.

The Columbia can be a harrowing dive spot, but Holcom relishes in a challenge.

‘Then it’s second nature’

Christie Davis took over the shop from Floyd in 2022.

Astoria Scuba and Adventure Sports now distinguishes itself as the only dive shop directly on the Oregon and Washington state coasts.

The breadth of their work extends far beyond recreation, too. The shop supports and supplies operations by the Astoria Fire Department and the U.S. Coast Guard.

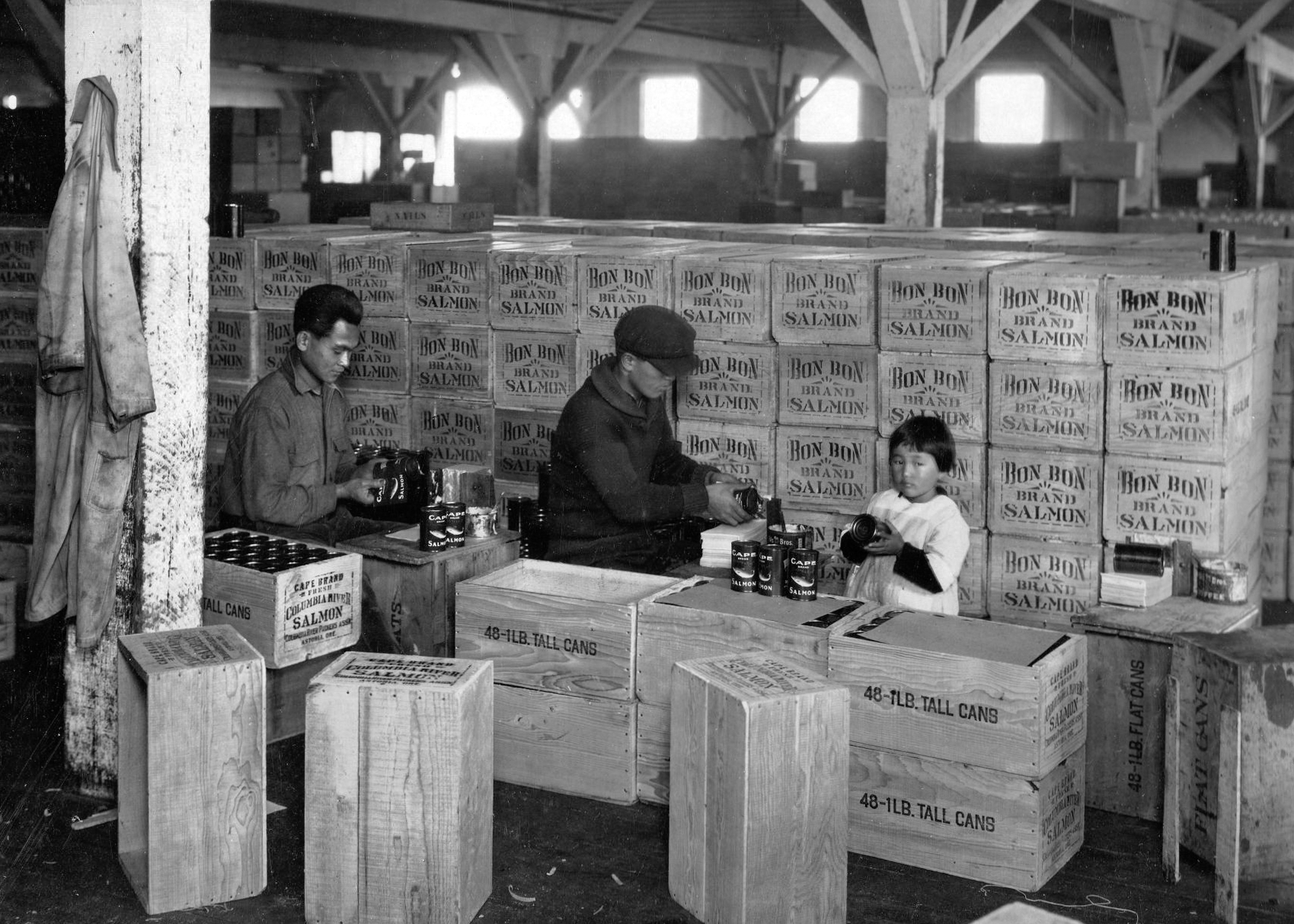

Many workers in Astoria canneries during the late 19th century were Chinese immigrants. (Clatsop County Historical Society)

Davis and her team are also guides for the certification process that tightly regulates scuba diving. Becoming a diver can be a daunting prospect, but Davis said it’s a step-by-step process designed to make people feel comfortable in an uncomfortable environment.

“You have a good instructor that works you through it,” Davis explained. “Then it’s second nature.”

Training takes place online and at a local pool. Once certified, divers can even join one of Davis’ dive tours in the Puget Sound or Hood Canal, places much better suited than the Columbia for novice-level divers.

“I wish we could dive right here,” Davis said. “But you can’t see your hand in front of your face and the currents are outrageous.”

She noted that Holcom has dove right here. He even found an old shipwreck that hit a rock and sank just a stone’s throw from the dock of the pier.

Davis is also effusive about how hard Holcom fights for the survival and future of not just the old buildings, but the pier’s tenants.

“Floyd is very much about promoting people’s small businesses,” Davis said, noting that many of those businesses are women-owned.

It’s little wonder that Davis flows seamlessly between serving recreational divers and turning to the highly specified needs of rescue divers the next. Retired from the U.S. Navy, Davis used to spend her days tracking submarines as an ocean systems technician. Now, she’s happy to be providing a different kind of service.

There are multiple levels of dive certification, and Davis notes local instructors are well equipped at any level, seeing as they are retired Army combat divers. “We do what we can to support our special forces,” she said.

While there are much warmer, more favorable places to learn to dive, Davis said becoming certified in the Northwest environment will set you up for success almost anywhere.

“If you learn to dive in the Pacific Northwest, you’re going to be a good diver,” Davis said. “This is one of the most challenging places to dive in the world. We take a little bit of pride in that.”

Historic treasures

Wander down the way from Davis’ dive shop to encounter a bevy of wooden boats and other maritime artifacts from the time of the cannery’s heyday.

The Hanthorn Cannery Museum, while largely self-interpreting, is a stockpile of historical treasures, imagery and stories from those heady days of massive hauls of salmon and mountains of tuna.

The museum tells the story of the pier, built in 1875 as the Hanthorn Cannery, eventually morphing into the Columbia River Packers Association and finally to Bumble Bee Tuna, once Astoria’s largest employer.

Pieces of memorabilia are scattered throughout the pier, like this sign for Bumble Bee Seafoods with the tagline “work is our joy.” (David Plechl)

For creator and curator Peter Marsh, the museum was an accident — an unintentional collection of items diverted from the dump or flea market. It has become a reflection of his affection for all things maritime, especially the faded, forgotten and lost.

Displayed here is the scale of what was at stake — a decadeslong harvest that would create livelihoods for many and fortunes for few. The wealth captured from the river funded Astoria’s growth, and while this pier was but a piece of that, it is one of few buildings like it left.

Marsh grew up on the outskirts of London. Fascinated by boats at an early age, he only saw the inside of his first proper sailboat while on a cycling tour at 16 years old.

But boats were more than physical things, he remembered. They were a measure of one’s bravery and skill.

“If you hadn’t sailed to France in a small boat, you were a chicken,” Marsh recalled.

Marsh would come to travel almost exclusively by sailboat or bike. And it was on another bike ride, this time from Mexico to San Francisco, that he came upon a spark of inspiration in the form of a maritime museum.

“It was just a museum dedicated to fish and maritime. I never dreamed you could have a museum of just pictures of fishing,” Marsh said.

When asked about the first time he stepped foot on a boat. He mentioned perplexingly that he’d never set foot on a boat. He then said in passing that he’s not been up to much, only to plop down his freshly published, hefty tome of a book, “Liberty Factory” — a story of merchant vessels built in Oregon during World War II.

Marsh seems to follow the wind, or maybe the light. He appears to navigate by a small constellation of interests — boats, bikes, history and language. Traveling light means few possessions, and Marsh instead has concentrated his efforts on saving things that tell a story, even if it’s not his.

Most of the artifacts in the Hanthorn Cannery Museum’s collection were donated (an old wooden gillnetter), diverted from their path to the dump (antique canning equipment) or dusted off from some obscure storage closet (vintage Bumble Bee Tuna signage.)

In one room, a film from the 1960s plays on a loop, a trip back in time to the cannery’s boom days. Quirky as they may be, the displays pay particular attention to the workforce of individuals that were the lifeblood of the cannery’s success — an old locker with a hand-stenciled name, notes of the day’s catch tallied on a piece of scrap paper. Photographs of immaculately dressed workers tending to menial tasks with a striking dignity and poise.

Taking in the rich jumble of history displayed here, its waves of hopeful immigrants, and the innovations and ingenuity indicative of this gritty time gone by, Marsh seems newly inspired.

“It was a hollow place,” he reflected. Thanks to Marsh, it isn’t anymore.

A cauldron of crab

Across the breezeway from the museum, Bill Hagerup, owner and proprietor of OleBob’s Seafood Market, is boiling a cauldron full of crab. They go for about $20 apiece, and he estimates he’ll sell about 15 to 20 Dungeness a day.

Originally from Astoria, Hagerup labored for years as an electrical engineer in Portland.

“After I retired, this opportunity came up,” he said.

Hagerup has been at it for a little over a year and simply feels at home on the pier. His live crab tank can hold up to 1,500 gallons and 350 crab. Once crab season is up, he’ll shift his focus toward salmon, oysters and clam chowder.

Bill Hagerup boils fresh crab at OleBob’s Seafood Market. After an engineering career in Portland, Hagerup returned to Astoria and has relished in the community he has found on the pier. (David Plechl)

Fishing for his family goes back three or four generations. His dad was a teacher and would fish in the summer. Running a seafood business at Pier 39 is a kind of homecoming for Hagerup. He spent most of his childhood here but hadn’t lived in Astoria since 1981.

“Astoria has just changed so dramatically,” he said. “But it still has that working-class feel I love. And it’s just spectacularly beautiful.”

Hagerup had run a few other seafood businesses around the Columbia-Pacific region, but Pier 39 has been the best fit for him.

“I like being part of the small business community here,” Hagerup said. “We help each other out.”

‘Full of stories’

Helping each other out is the name of the game for Stacey Stahl, owner of Menagerie on Pier 39 as well as the Mess Hall Market.

She is a self-ordained promoter of all things Pier 39 but sees the pier’s people as its greatest resource. Here, Stahl has found a sense of camaraderie.

“You can feel the history when you walk on the pier,” Stahl said. “This place is full of stories.”

Ghost stories, too. More than one person has reported encounters. But don’t worry, these specters are said to be less of the spooky type and more of the prankster.

That hasn’t stopped Stahl from running her shops. Wander through to find regional foods, handmade jewelry, ceramics, soaps, fine art and even Bumble Bee Tuna. “That’s why she calls it Menagerie,” suggested Stahl’s right-hand woman, Claudia Price.

“She’s such a dynamic person,” Price said about Stahl. “Her brain is always working.”

A new canvas

About 17 years ago, Susan Schroeder was semi-retired and looking for a new opportunity. Holcom was looking for someone, anyone, who might be interested in doing custom canvas and fabrication work on the pier.

That was the start of Four Winds Canvas Works. Housed in what was once the ammonia-filled heart of the old cannery’s cooling system, a maze of piping still crisscrosses overhead.

“It sounded like a great idea,” Schroeder said, “and no one else was doing it.”

Susan Schroeder had just opened her sail repair and fabrication shop, Four Winds Canvas Works, when a storm packing fierce winds ripped up the Columbia River. Needless to say, she was suddenly very busy. (David Plechl)

Not long after opening her doors, The Great Coastal Gale of 2007 tore up the Columbia, through the docks and mooring basins, with devastating results.

Schroeder spent the next year repairing sails, canvas covers and upholstery damaged by the storm. If she was learning when she started, she was an expert by that year’s end. And the work kept flowing in.

But every job is different, and with customization the standard, Schroeder is never sure exactly what’s coming next. Like the day a young woman came knocking at her door, looking distressed and trying to communicate in broken English. It wasn’t going well until the woman started pointing to a photo of a sail, and Schroeder soon gathered what was needed — another sail repair.

Turns out the woman was on a round-the-world sailing adventure from China, with a sizable crew that was stranded. Schroeder called Holcom for help, which was fortunate as he turned out to be fluent in Mandarin.

“We got the sail repaired and Floyd ended up hanging out with them, and they just gabbed, gabbed, gabbed,” Schroeder said.

Everything Schroeder makes or repairs is done with marine fabric and UV thread, so it’s meant to last. And nothing goes to waste. Decommissioned sails have been made into duffels, clam bags and even growler totes for a local craft brewery.

“We don’t throw anything away,” Schroeder said.

Across the way from Schroeder’s shop is the Rogue Public House. The lunch rush is fading, but Renee Stich is still busy at the bar, pouring pints and making drinks.

Above her head hangs a framed photo of a little old lady in a bathtub. Stich is happy to explain that that’s Mo, of Mo’s Chowder, who rented Rouge Public House their first spot in Newport. In exchange, every bar had to hang a picture of her in a tub.

But Mo also required they feed and take care of fishermen. Rogue is still doing that, with a full menu and over 30 rotating taps. Burgers are recommended, as are the cheese curds.

Seen from the river

Bobbing serenely, just below Rogue, is one of the cutest little boats you ever did see, and an agile one at that.

“On paper, this is the dumbest thing in the world,” said Mark Schacher about the business he has run since 2020, giving rides aboard his retired pilot boat, Arrow No. 2.

Self-employed, Schacher ranks himself among an exclusive group he describes as, “the only people working 70 hours a week, so they don’t have to work 40.”

As a kid growing up in Astoria, he remembered playing on the log rafts and waving at the passing log tug drivers. He then grew up to be one.

After working as a log tug driver, Mark Schacher moved into the construction field. Now, he’s back in a boat, launching tours from Pier 39 aboard the Arrow No. 2, a retired Bar Pilot boat. (David Plechl)

Astoria’s Pier 39 is a living connection to the city’s canning and seafood history. (David Plechl)

But times and methods changed, and Schacher was laid off from his job in the 1990s when the use of logging tugs was largely abandoned.

“I towed the very last log raft out of the Lewis and Clark River,” he said.

Schacher moved on from driving boats. Got into construction. Ran a water district. Built houses. But along the way he always had some kind of boat, but nothing quite like Arrow No. 2.

Since relocating Arrow No. 2 to Pier 39 from a dock downtown, he estimated he’s seen three to four times as much business. No surprise, the retired pilot boat — with its smooth curves and simple wood-framed windows — doesn’t look a step out of time in front of the old cannery.

And on this particular day, Schacher prepared to launch another group out into the vastness of the river, while admiring the seven coats of fresh varnish Job Corps cadets had applied to the deck the day before.

The Arrow No. 2’s relatively diminutive size belies a turbo-powered diesel heart and a 48-inch propeller that can swing a ship at anchorage.

Maneuverability has to be the hallmark of a boat whose core duty involves performing that heart-stopping approach upon towering tankers — something like a bird landing on the back of a running rhinoceros.

Arrow No. 2’s service as a pilot boat spanned 50 years, beginning in 1962, shuttling tens of thousands of pilot transfers. Schacher thinks that because of its long lineage (and its good looks) Arrow No. 2 may be one of the region’s most photographed boats.

He made one change after taking ownership — adding 10 feet to the back of the house for a bathroom. Oh, and he added a few old iron steps that were once used inside the Astoria Column.

“I just saw ’em out in the blackberry bushes,” he said.

And just four years before the boat was retired, it got that new engine. With a lot of miles left to burn, and a lot of space between now and then, Schacher is filling the hours the best he knows how, by running the boat and working the river.

On this mild evening, his wife, Jennette, and son, Paul, were along for the ride. Jennette was eager to try out a new camera, but by the end of the boat ride it was Paul who had caught the shutterbug.

And there was plenty to photograph as the boat wiggled its way from Pier 39 down through the West Mooring Basin — serenaded on both sides by barking and braying sea lions.

As Arrow No. 2 slipped down the shoreline, past the old net shed, Big Red, beyond pilings and abandoned docks, Astoria’s connection to the river became clearer, that without it the town couldn’t exist, wouldn’t have existed.

Pier 39 is a relic of that bustling waterfront, where dozens of canneries once thrived. As Arrow No. 2 approached the Astoria Bridge, Schacher pointed out where Bumble Bee Tuna’s main processing plant once stretched proudly along the shoreline.

All that remains are pilings and a cement foundation where one of the old cannery’s furnaces once glowed hot, and possibly where the fire started that claimed the cannery in the late 1990s.

The tour moved on toward Astoria’s last remaining seafood processing plants, near Clatsop Spit. But on Sunday night, the fishing boats that sometimes gather by the dozens were nowhere to be seen.

No problem, Schacher’s guests were still wide-eyed and beaming as the boat glided back beneath the arching Astoria Bridge as the saturated shades of the day’s waning light played among the river and sky.

After that, sailing between the behemoth ships anchored off the channel and rounding the rugged and densely forested Tongue Point, the sky darkened, and Arrow No. 2 floated back toward Pier 39, where it was soon tied up and tucked in. The evening’s first stars had appeared. Amidst fading chatter and fleeting hugs, the tour had ended.

As the winter months drew near, Schacher knew he’d be getting fewer calls. On paper, he may be right. This might be the dumbest thing in the world. Like trying to sustain life and myth in an old building that a huge river and hungry winds are always trying to swallow.

But still, Schacher insisted — it’s somehow worth trying.