Bookmonger: A poetic elegy for generations past

Published 9:00 am Tuesday, March 19, 2024

- “The Pear Tree,” by Edmonds, Washington, poet Bethany Reid, pays homage to a southwest Washington farm that was home to three generations of her family.

The late Sally Albiso didn’t devote herself fully to poetry until she moved to the Olympic Peninsula to retire in 2003.

Trending

But then she had the inspiration and made the time to dive in: writing poems, winning a fair share of poetry contests, and finally seeing her full-length volume of poetry, “Moonless Grief,” published in 2018. A year later, she passed away.

In a tribute to his wife and her dedication to her craft, John Albiso arranged with MoonPath Press to endow The Sally Albiso Poetry Book Award, an annual opportunity open to poets living in Oregon, Washington and Alaska.

Since 2019, winners have received a cash award and publication of their poetry by MoonPath Press.

Trending

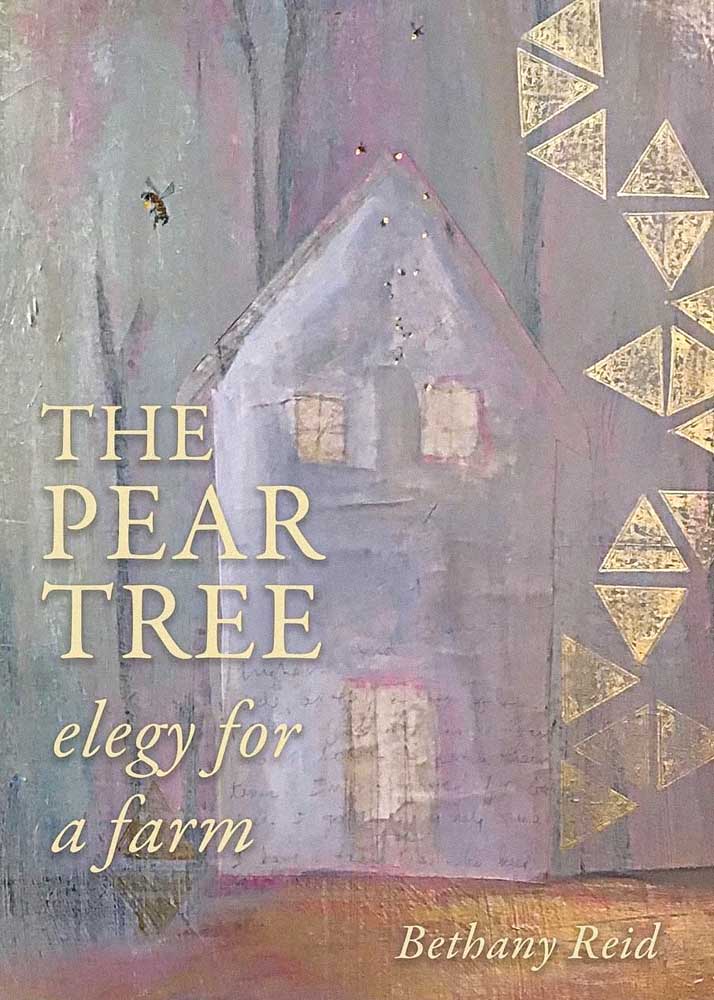

“The Pear Tree” by Bethany Reid

MoonPath Press — 90 pp — $17.99

The recipient of the most recent award is Edmonds, Washington, poet Bethany Reid. Her volume, “The Pear Tree,” pays homage to the southwestern Washington farm that had been home to three generations of her family.

Her grandparents homesteaded the acreage, planted an orchard, grew crops and raised livestock — and 15 children.

Eventually, the farm passed on to their 11th child, Reid’s mom, who married a logger. That couple propagated their own passel of kids, raising them in the Pentecostal faith, and kept cows, horses, chickens, pigs, dogs and feral cats.

All this is fodder for Reid’s poems — the fields, the trees, her grandfather’s beehives, her grandmother’s butter knife. The relations who lived to old age, and the ones who died too soon.

Reid remembers the farm her grandparents tended, but also recalls the acreage as it grew “back in trees, seedlings sprouting / in hayfields.”

Time claims not only fields and lives but other things, too: a pickup truck swallowed up by briars, “dwindling summer creeks,” an old dictionary left in the attic, “pages glued together from P / to T by the steady drip of decades,” even railroad lines and old sawmill towns.

In Reid’s mother’s case, time erased memory.

In a poem titled “The Last Time I Heard Her Play the Piano,” the poet writes about witnessing the gradual onset of her mother’s dementia, how her mom’s memory seemed to be “a companion stepping aside on the trail / while she walked on.” And yet on random occasions, “as if her dementia had been called out of the room / by something more urgent,” her mother could sit down at the piano and play, “forgetting her forgetting.”

One iconic symbol abides throughout the pages of this book and the generations: the pear tree planted by Reid’s grandmother. In the book’s opening poem, “The Pear Tree in Winter” endures despite “ice-burdened branches.” In late spring it presents “a frenzy of blossoms” with “limbs raised, bursting with bees.”

And even when the third generation finally closes up the house for good, that tree is standing sentinel out in the yard, laden with fruit a century later.

In these affecting poems, devastation is mitigated by beauty, lamentation is laced with love, and memories live on.