Bookmonger: Of rivers and ‘deadbeat dams’

Published 9:00 am Tuesday, January 2, 2024

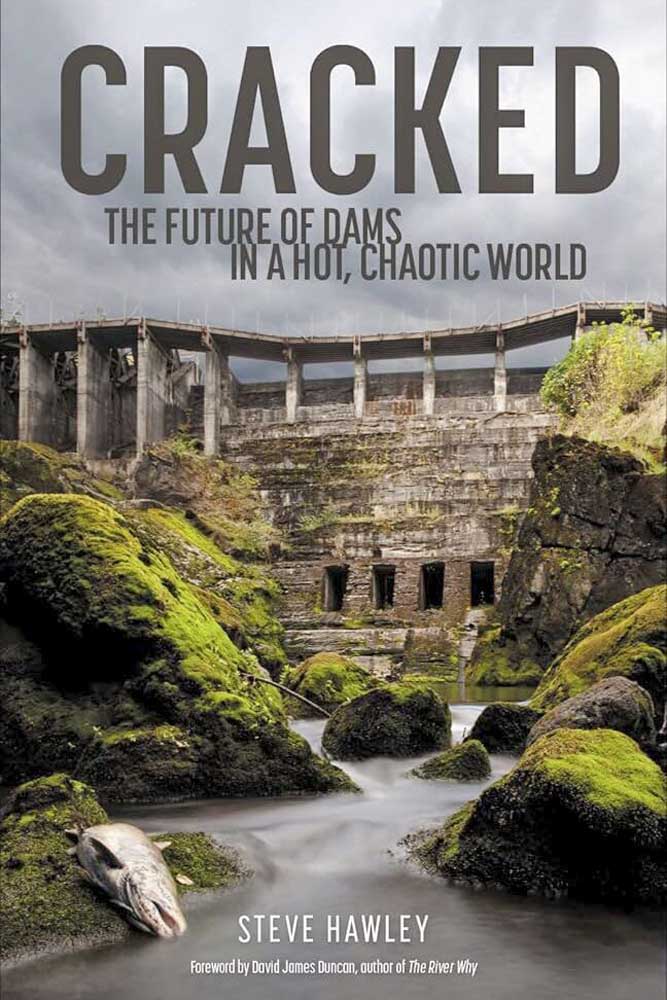

- Steve Hawley’s “Cracked” explores the history of and challenges associated with dams along Northwest rivers, including on the Columbia.

Steve Hawley grew up in Portland, just a bike ride away from the Columbia River. Today he’s become one of the leading advocates for reversal of U.S. dam-building efforts over the last century.

Trending

In recent months, the environmental journalist and filmmaker has been traveling the country to talk about his new book, “Cracked,” subtitled “The Future of Dams in a Hot Chaotic World.”

Using the river he grew up next to as the poster child for never-fully-vetted water control projects, Hawley marvels at history’s “army of government engineers insisting on a nature contained in straight lines to make it calm, sane, predictable, profitable, productive, and amenable to the demands of civilization.”

Sure, harnessing the Columbia has helped farmers make the desert bloom into orchards and wheatfields, and did provide the water needed not only to cool nuclear waste at the Hanford site but also to electrify the region with cheap hydropower.

Trending

“Cracked” by Steve Hawley

Patagonia Books — 322 pp — $28

Yet the economic and military-industrial benefits accrued over the last century have nearly obliterated the river’s original resource — a millennia-old legacy as the world’s largest salmon run — and that’s led to a domino effect diminishment of cultures, human and otherwise.

Among his many arguments against dams, Hawley points out that they contribute to climate change and its impacts. For starters, they emit significant amounts of methane.

Also, they’re inefficient. Studies over the last half-century demonstrate that evaporation of slack-water impounded behind dams often exceeds the amount of water consumed by dam customers.

Another disturbing consequence: gigatons’ worth of river sediments have been trapped behind dams over the last several decades.

While unfettered rivers deposit sediments that create bars and marshes at their junction with the sea, providing natural barriers to storm surges and high tides, a dammed river can no longer nourish the coastline at its mouth. Not only does the vitality of the coastal ecosystem suffer, but longtime beaches sometimes disappear altogether.

On the brighter side, Hawley points to examples of the Elwha and White Salmon Rivers in Washington state, where dams have been dismantled and the rivers have largely self-repaired.

The author has also reviewed the yearslong Klamath Basin water wars along the Oregon-California border, which involved fishermen, farmers, public utilities and Indigenous groups and were further complicated by high-level political meddling.

Finally, negotiations led to a plan for removing four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River.

The first dam was dismantled last summer, just after “Cracked” was published. The other three will begin drawing down their reservoirs in January in preparation for removal next summer.

Hawley writes with passion, but in a “Dam Removal 101” chapter, he reminds us that this type of advocacy requires patience. It requires “door-to-door diplomacy, a revival of the practice of community-level democracy … “

This book’s impact is underscored by glorious full-page, full-color photographs of rivers and dams. They illustrate monumental feats of engineering undertaken by humans — that in the end haven’t measured up to nature’s inexorable drive. Photo credits include mention of the ancestral lands where these rivers run — it’s a meaningful gesture.