Bookmonger: Three generations across two continents

Published 9:00 am Wednesday, February 8, 2023

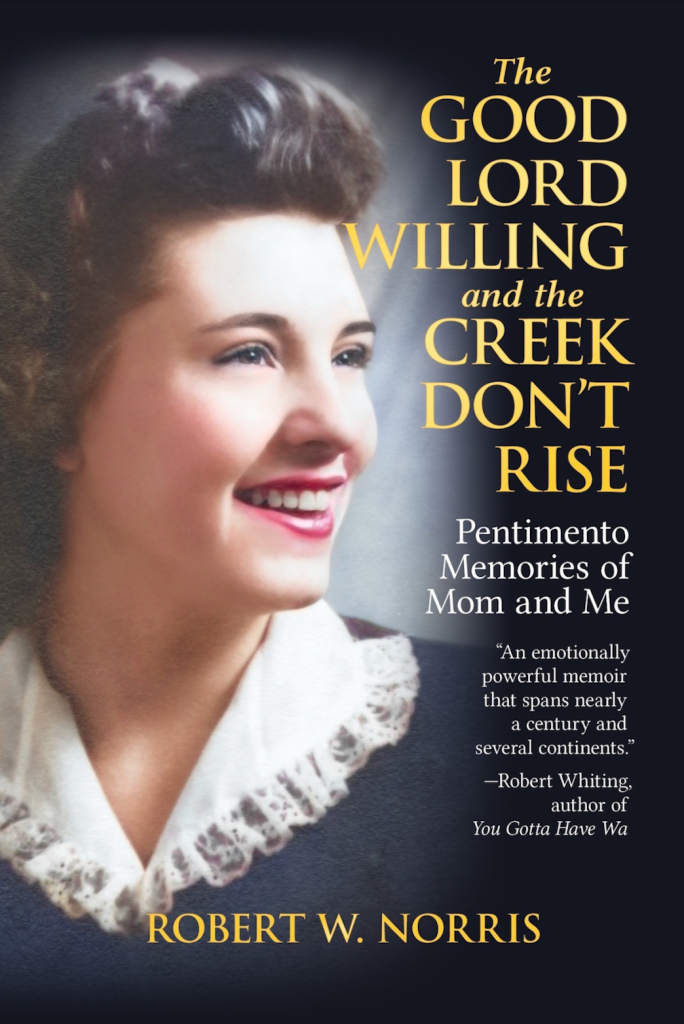

- ‘The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise’ is by Robert W. Norris.

The Northwest has seen influxes of different groups of immigrants from Asia over the years, and this column has featured books that have covered the opportunities and challenges that have been faced by folks who were caught up in those diasporas.

Trending

But the story we’ll take a look at this week focuses on a different quest for opportunity and a new home — one that takes an American to Asia.

Robert W. Norris’s memoir, “The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise,” covers his West Coast childhood, a rebellious adolescence and a stint in the U.S. Air Force that was cut short when he became disaffected with the Vietnam War and identified as a conscientious objector.

That led to a court martial and stint in military prison, which resulted in being renounced by his father’s strait-laced side of the family. But Norris’s mom — somewhat of a renegade herself — was more understanding.

Trending

“The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise” by Robert W. Norris

Tin Gate — 490 pp — $21.99

This book’s subtitle is “Pentimento Memories of My Mom and Me,” and the book begins with his mom’s vibrant memories of growing up along the Columbia River in White Salmon, Washington as the daughter of Midwestern farmers who had fled hard times in the Dust Bowl.

Kay Murphy Schlinkman learned to stand up for what she believed in, even if that meant calling out a priest in front of his congregation when he refused to give her communion or, later, confronting the Lieutenant Colonel who was court-martialing her son. She imparted these home-spun lessons of independent thinking to her kids, too.

When Norris was released back into society, he wandered across the country in a “nomad daze,” and through the counterculture as a “druggie anarchist.” He worked in restaurants and on oil rigs, hanging out with high school pals, ex-cons, veterans, poets and fellow self-styled seekers.

Eventually his wanderlust took him to Europe and further east to Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and India. Another trip took him to Hawaii, and then — with only $100 in his pocket — to Japan, where he found a temporary job as an English teacher, but ultimately discovered a culture and country to call his permanent home.

Even so, he has returned to the Northwest repeatedly, because it figured so prominently in his mom’s life. The final pages of Norris’s book find him spending a lot of time back in the Portland area – sometimes physically and other times virtually – as his mom reaches the end of her years.

This memoir is far-ranging, both geographically and philosophically. It’s clear that Norris has been an assiduous note-taker throughout his life. In exacting detail, he recounts hallucinogen-induced theological discussions as a young adult, the professional tussles in his career as a university professor in Japan, and the medical minutiae of his (and his mom’s, and his wife’s, and his sister’s) senior years.

Yes, some of this comes across as a case of too much information. But even so, “The Good Lord Willing” divulges generational stories worth hearing about and world views worth considering.