Bookmonger: One family, a century of social policies

Published 9:00 am Wednesday, November 30, 2022

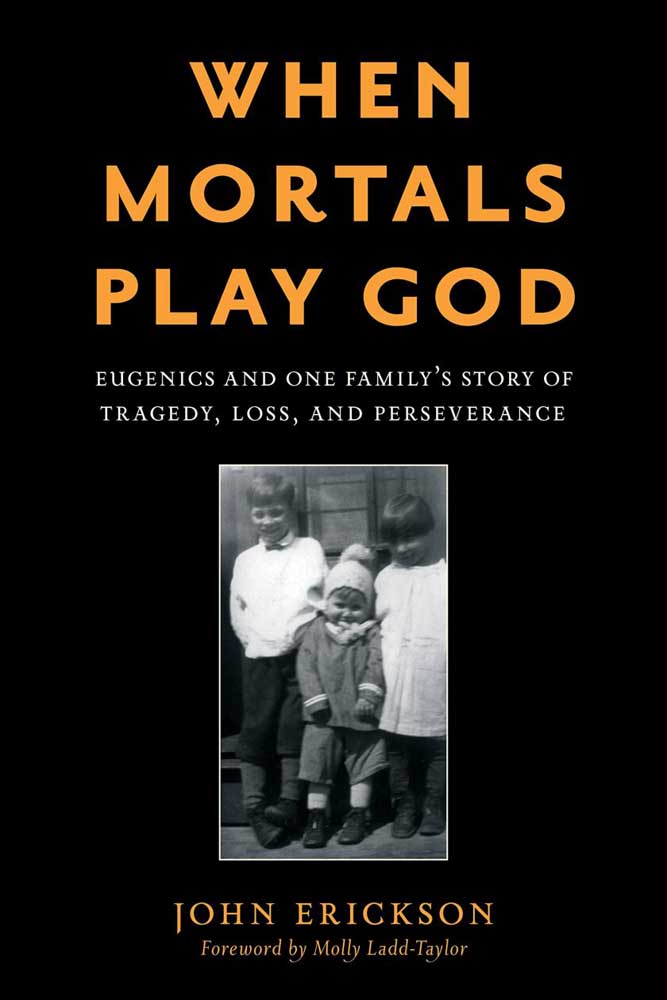

- “When Mortals Play God” tells the story of journalist and author John Erickson’s forays into genealogical research.

In his new book, “When Mortals Play God,” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist John Erickson applies his research and reporting skills to look into what may have contributed to generations of misfortune and heartbreak in his own family.

Trending

The 20th century’s evolving approaches to mental health, intellectual disabilities, developmental delays and criminal behaviors – all of that gets sucked into this cyclonic history.

“When Mortals Play God” by John Erickson

Rowman & Littlefield – 224 pp – $36

Trending

While many of Erickson’s ancestors’ calamities occurred in the upper Midwest, one branch of the family eventually departed for the West Coast, where they sparked their own fireworks in Portland and Astoria. But that comes later in the story.

Erickson’s grandmother, Rose DeChaine, was born into a large Minnesota family in 1901. She was a willful child, and from a young age, got expelled from school repeatedly, until – while still young – she never went back.

Rose drank heavily, married often and gave birth to three kids by three different fathers. The third baby was born while Rose was institutionalized in the Faribault School for the Feeble Minded. Her kids were sent to a Catholic orphanage and Rose, in accordance with Minnesota’s eugenics laws, underwent a sterilization procedure.

Yes, it was as Dickensian as it sounds. The term ACEs, an acronym for Adverse Childhood Experiences, wouldn’t arise until the very end of the 20th century and, with it, an understanding of ACEs’ causal effects on chronic, toxic stress.

In the meantime, Rose and her children were subject to the limitations, and sometimes the horrors, of the institutions at the time. Erickson, one of Rose’s grandsons, tries to uncover the unspoken secrets of his ancestors to try to understand how life went so terribly awry for many in his family.

“When Mortals Play God” is, in part, a recitation of the genealogical forays Erickson made as he tracked down records and reports in newspaper archives, hospitals, prison systems and the military. (This will be interesting for genealogists, but may be tedious for other readers.)

There’s also an array of historical family photos. Yet for all of the author’s careful attention to detail, one element is noticeably lacking in this book. The inclusion of a family tree would have been very helpful in tracking this story of multiple generations, multiple husbands and many cousins.

This true story contains plenty of drama – accidents, state-ordered intrusions on privacy, illicit liaisons and other tragedies. But what shines through the most is the shortcomings of many of 20th century America’s institutions – educational, charitable, legislative, legal – in providing or denying services to those in dire need.

A courtroom killing in Portland in 1979 and a bombing plot and suicide in Astoria in 1995 underscore the long legacy of abuse that has bedeviled this family. And yet, whether through grit, faith or encounters with kind-hearted individuals along the way, some of the DeChaine descendants persevered and even flourished.

This book may prompt readers to consider what’s needed to improve current systems that are designed to confront and allay the legacies of suffering we see around us.