Bookmonger: Punk rock and trauma inform two memoirs

Published 9:00 am Wednesday, June 1, 2022

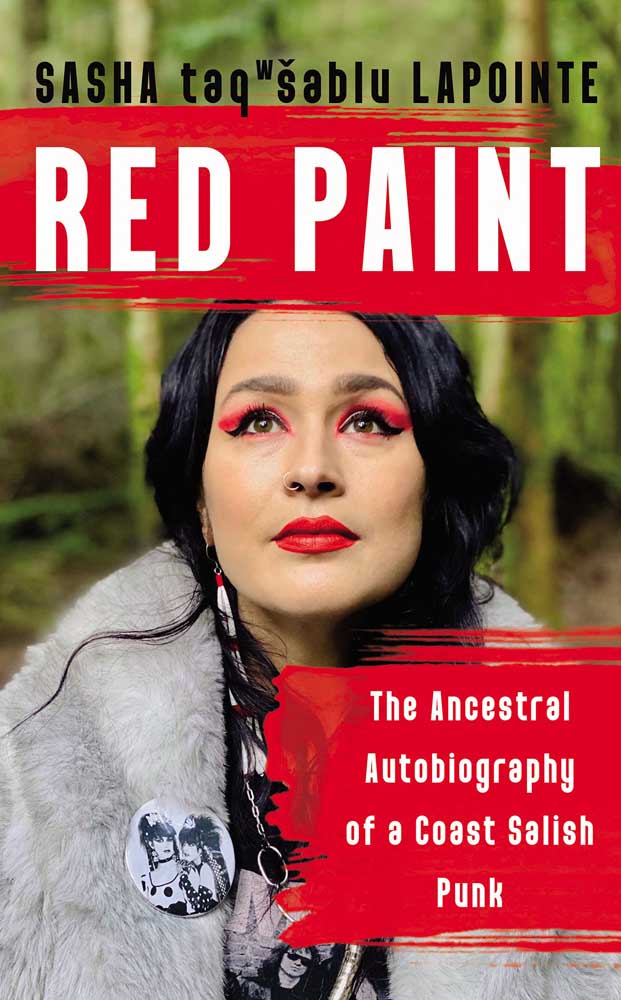

- ‘Red Paint’ is by Sasha taqʷšəblu LaPointe.

‘Possums Run Amok,’ by Lora Lafayette

Mercuria Press – 176 pp – $16.95

Trending

‘Red Paint,’ by Sasha taqʷšəblu LaPointe

Counterpoint – 208 pp – $25

Completely independent of one another, two Northwest women have written memoirs that chronicle many similar elements – trauma-informed adolescence, a punk rock soundtrack, drug and alcohol use, sexual awakenings that include experimentation across genders, travels to Europe, marriages that don’t work out and pregnancies that result in miscarriage. Yet for all the similarities between these books, each is a wholly distinctive work.

Portland author Lora Lafayette’s new book, “Possums Run Amok,” follows what seems to be a regional talent. Portland writers seem to come up with some of the best book titles around. The subtitle promises ”a true tale told slant,” and the way Lafayette writes her memoir, there is definitely a Dickinsonian dose of ecstasy, minus the guarded 19th century mystique.

Lafayette’s life is an itch in search of the right scratch. It is jumpy, dreamy, wild and at times scarily sane. This book conveys voracious and often reckless appetites. Lafayette feeds not only on punk music, but also Borodin and Brahms and The Partridge Family, baguettes and canned chili, Vladimir Nabokov and Lewis Carroll, hashish, LSD, coffee and cigarettes.

Eventually, when schizophrenia manifests, Lafayette’s life revolves around suicidal ideations and prescribed medications.

“Possums Run Amok” is an inventive frenzy of images and impressions. It is frightening and funny. It’s heartbreaking, sometimes exhausting, a unique voice.

Then, there is Sasha taqʷšəblu LaPointe’s gracefully written new memoir, “Red Paint.”

LaPointe’s Skagit middle name was a gift from her great-grandmother Vi Hilbert, a tribal elder of the Upper Skagit who became renowned across the Northwest for playing a major role in reviving the Lushootseed language and culture.

This is a proud legacy to carry forward, as is LaPointe’s direct lineage to Comptia Koholowish, one of the few among the Chinook who survived a smallpox outbreak brought about by the region’s first white traders.

But that historical footnote hints at other more recent and less salubrious legacies. Poverty and abuse have affected Indigenous groups since colonizers first began asserting their dominance across North America, including here in the Northwest.

LaPointe’s childhood and adolescence were marked by this generational trauma. In “Red Paint,” LaPointe writes about how she has struggled to heal from these collective traumas, self-medicating as a teen and battling deeper mental depression and physical ailments as she grew older.

But LaPointe is also descended from a long line of medicine workers. As a child, the red paint she saw her elders wear in ceremonies indicated their station as healers, though wearing red paint can’t happen without permission. To have permission, one must be worthy.

Fighting to find her own voice through poetry and punk, and through heartfelt but ultimately incomplete romances, LaPointe learns how to honor her legacy, building a sense of identity and self acceptance.