Fish, family and the ties that bind

Published 4:00 am Thursday, August 13, 2015

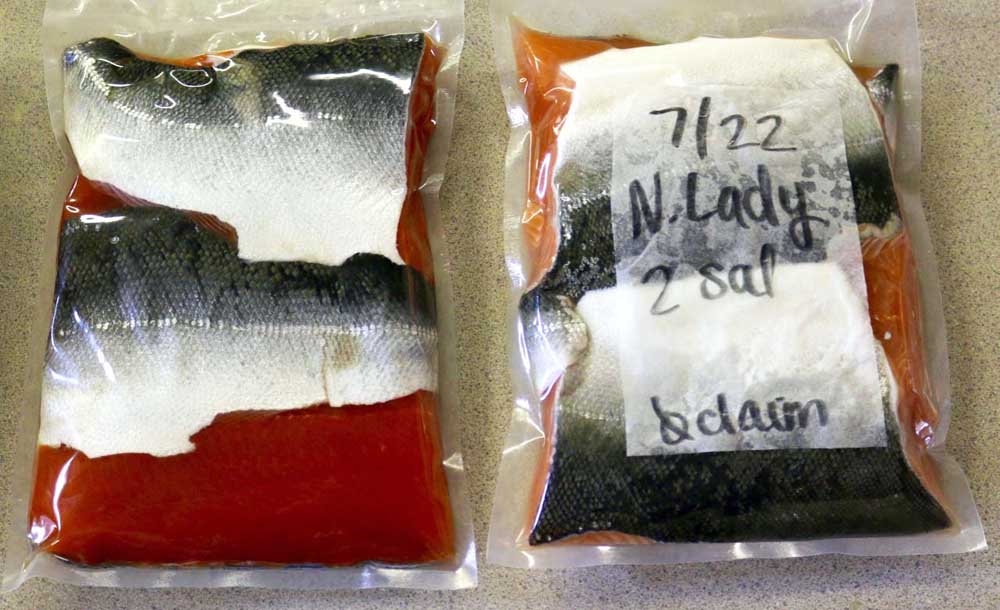

- Fresh coho salmon, vacuum packed at the Sportsmen's Cannery in Ilwaco, Washington.

Tina Ward was penniless and unemployed the day she stepped from the bus in Seaview, Washington, and headed in to apply for a job as a fish processor at the Sportsmen’s Cannery.

It was an act that would shape and change her life forever, but of course, she couldn’t have known that then — when you’re only 13 years old, the moving hand of fate can be pretty hard to recognize.

More than three decades later, sitting outside the same cannery, now as its owner, she laughs about that long-ago summer day: “It was time to think about school clothes for the fall, and I wanted something fancier than what we could afford. My mom told me, ‘When you’re making your own money, you can buy whatever you want.’

“Well that was the only opening I needed,” Ward recalls, rolling her eyes at the thought of her young, overly-ambitious self. “I took it to mean that it was just fine for me to go out and get a job. So I hopped on the transit, and that’s exactly what I did.”

Opened in 1943 by Roseanne and Lefty Leavers, the Sportsmen’s Cannery does what the name implies — it’s the place where any sport fisher can bring a fresh catch for processing, and have it returned to them, no minimum required. In the earliest days, the business sustained itself mainly on razor clams, cleaned and cooked; but through the years, more and more services were offered, always alongside the cannery’s signature seller: Pacific albacore tuna.

When it changed hands for the first time in 1978, it was purchased by the Brophy family, who pledged to offer the same fine service as their predecessors and to continue the company’s original promise: “Your own fish back since 1943.” Eventually, the family added a second seasonal location at the Port of Ilwaco, expanding their commercial buying operation for tuna and salmon, and offering dockside services that made it easier to cater to the charter fishing crowds.

When a teenage Ward entered the scene in 1982, it was the height of salmon season, the busiest time of the year. And while most kids would have been put off by the thought of handling fish all day, for her, it was a perfect dream.

“I loved everything about it,” she says. “The work, the fish, the customers, the paycheck, all of it — I couldn’t get enough.”

Working summers and vacations at the cannery through junior high and high school, Ward saved her money — first for those designer jeans, then for a car, then for college — eventually going away to Spokane, Washington, where she enrolled at the university with a major in pre-medicine.

But every summer she came home: back to the Long Beach Peninsula and back to the Sportsmen’s Cannery.

Between her sophomore and junior years, spending all day at the cannery and all night at a second job waiting tables, Ward found little time for much besides work. Yet somewhere in the middle of it all, she managed to fall in love with a young man named Kevin, and by summer’s end, the smitten couple faced the ultimate game changer — an unplanned pregnancy, and with it, some tough decisions.

Kevin Ward’s hands are almost a blur as he presses the thin blade of a fillet knife along the spine of a coho salmon, deftly maneuvering it through the bright flesh with one seemingly effortless pass, just as he’s done more than a million times before. Looking up from the butcher table, he catches a glimpse of his oldest daughter, Sydney, now 22, and cocking his head a little to one side, flashes a grin before saying, “You know, it’s all about the women in my life.”

It’s obvious he means it and only in the best of ways; in all respects, he looks like a man who can spot something good when he sees it.

“I didn’t know much,” he says, thinking back to that first summer with the woman who would become his wife, “but I was at least smart enough to realize that if I hung onto Tina, she’d see us through.

“Now don’t get me wrong,” he adds, “I work hard. But I’ve never met anyone who can work like she does. I’m telling you, she’s a complete powerhouse. All the women in her family are that way. I remember a few years back, it was a three-day (razor clamming) dig, and we had 750 limits to clean, so the whole family was pitching in. Tina’s grandma worked for 28 hours straight and her mom did 35. I made it to 37, but Tina, she saw it all the way through to the last clam. It was 41 hours, non-stop, and she was still standing. She’s the most amazing woman I’ve ever known.”

“For me, it’s like breathing,” says Tina Ward, of work in the cannery she seemed destined to own — an idea that became reality in 2001. “When the fish are here, we have to work. That’s just how it is, and I can’t help but love it.”

True to family form, she seems to have passed her genetic code straight down to both her daughters.

“My mom’s work ethic is fantastic, and I think watching that and learning how to work has definitely shaped me,” says Kempsey Ward, a 19-year-old student and the couple’s youngest, who, with her sister, spent formative years vacuum-packing fish and learning to operate the enormous pressure cookers that remain the mainstay of the family’s livelihood.

This summer, both girls are spending time home from college, working alongside their parents once more.

“She taught us that all the good things you want in life come from hard work and good choices,” says Sydney. “And I feel really lucky to have learned that at such a young age.”

Leaning in, Kempsey lowers her voice and looks once over her shoulder, the usual sign that a family secret is in the offing, only this time, the word’s already out: “Technically, both my parents own this cannery,” she says, a smart little smile playing at the corners of her mouth, “but really, we all know that it’s my mom’s.”

“I guess it’s that it’s always been such a big part of my life,” says Tina Ward, quick to admit her emotional attachment to the cannery. “It feels just like a family — all the tears but all the fun and laughter, too. It’s like an actual, living thing for me.

“But it was all my choice,” she adds, relinquishing her daughters from any pressure to take over. “I want them to find their own work in this life to love, and I don’t think this cannery is it.

“People have offered to buy it from us through the years, and my husband says, ‘Come on, isn’t there some magic number in your head that will do it?’ But the truth is, there isn’t. I can’t just hand it over to someone who doesn’t really know what it entails, or sell it to someone who thinks it might be charming to have an old cannery. Believe me, there’ve been plenty of times that I haven’t thought it was very charming.”

All around her, though, there’s evidence to the contrary: the same weathered cannery walls bear a classic whitewash over cedar shake; the same smokehouse churns out racks of alder-scented salmon, all done to tawny perfection; the same fishing floats festoon the entrance to a world that, thanks to this woman, has stayed largely the same for 72 years.

Tina Ward says she hasn’t met the next person destined to own her cannery. “But when I do,” she adds, “something tells me I’ll know it right away.”

Until then, whether you’ve caught it yourself or not, the same incredibly delicious products — fresh, frozen, smoked, sealed or canned — will continue to be the result of her family’s love and dedication to hard work.

And that’s good news for all of us.