Astoria artist juggles work, community, an in-progress master’s degree — and her time in the studio

Published 3:00 am Thursday, December 18, 2014

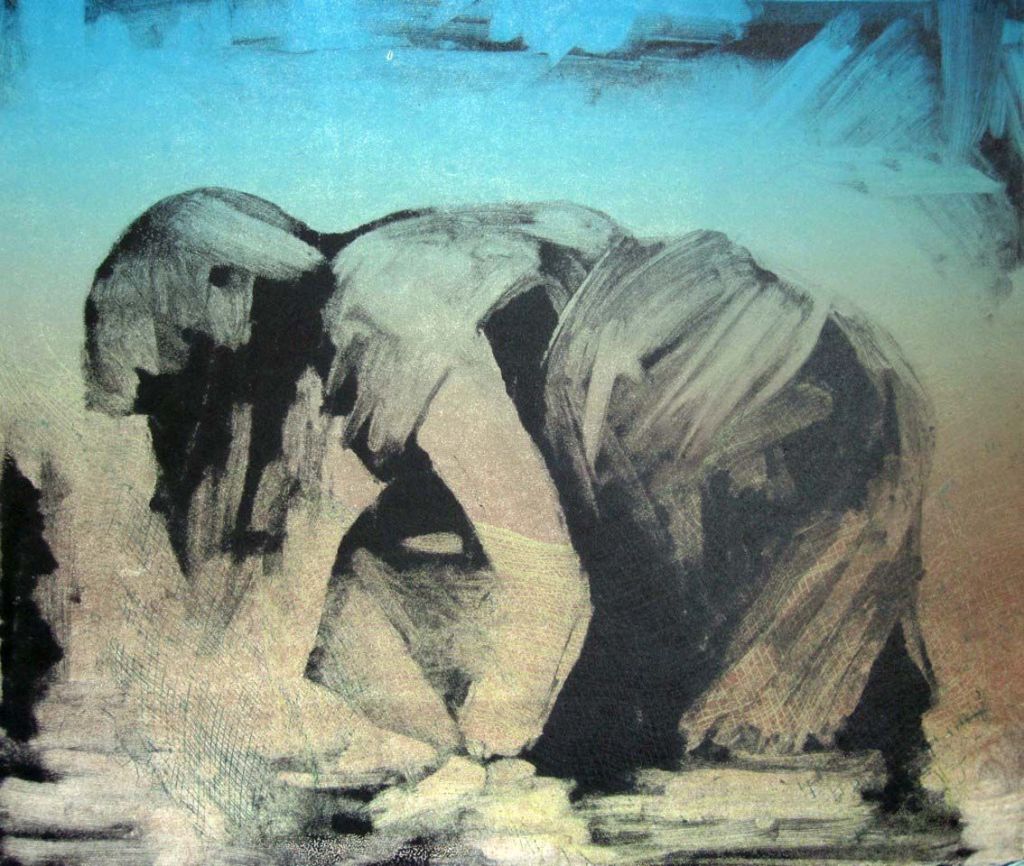

- “Erin” by Miki'ala Souza.

“I’m struggling with time,” says artist Miki’ala Souza. “How do I find time for it all?”

“All” includes school, her growing business as an artist, and her day job. When you visited Astoria’s River People Farmers Market last summer, she was one of the women who handed you a sample of zucchini salad at the Oregon State University Taste of Place booth. “I love working with the community and being a part of it,” Souza says. “I’ve worked for nonprofits and in school settings. It’s so important.”

Souza is also working on a master’s degree in art education at Western Oregon University in Monmouth. Fortunately it’s an online program, so she only has to visit the campus once a month. “It’s really important to be a practicing artist if you’re going to teach,” Souza says. No problem there. Her art has been on the Clatsop Comunity College’s gallery walls, and she has a new commission to create paintings to decorate a large building in Portland.

It isn’t unusual for a friend to be surprised to find out that Souza is an artist. She doesn’t make a big deal of it, perhaps because she’s never thought of herself as anything else. She grew up surrounded by art. “I’ve always enjoyed art,” she says, “My parents are both artists, and they’ve been very supportive.”

Souza is a native Hawaiian. Her mother, Cheryl Souza, teaches art history at Kapiolani Community College in Honolulu, where she has a reputation for being a good, funny and tough teacher; she’s also a fiber and ceramics artist. Souza’s father, Chuck Souza, is a lifelong musician and does ceramics and sculpture; his work was included in the CCC “Pacific Rim” art exhibit in 2013.

“My parents are clay people,” Souza says, “but I’m a painter, a drawer; my work is two-dimensional.”

After studying art at home and in high school, Souza was excited to explore the world outside Hawaii; she was ready for something else. She looked for a college on the mainland, but she thought that, after Hawaii, the east would be too cold, which is how she came to earn her bachelor’s degree in fine arts at the University of Oregon.

Souza’s other passion, in addition to art, is travel, “to see people and cultures around the world.” While an undergraduate, she spent six months at Parsons School of Design in Paris on a study abroad program. After graduation, Souza moved to Portland, and then spent three summers in the Solomon Islands observing art practices in a small village, as an employee of a project funded by the National Science Foundation. She has been to New Zealand three times and received a grant from the Oregon Arts Commission for the latest trip, for residencies and exhibitions at gatherings of indigenous artists.

When Portland began to seem too inland, this island girl decided it would be a nice idea to spend a summer on the Oregon Coast, which is how she arrived in Astoria. That was four years ago, and she hasn’t left.

In Astoria, Souza learned an enormous amount from the late Royal Nebeker. Up to that time Souza had been primarily a painter, but Nebeker enthusiastically told her, “Now you’ll become a printmaker.” She took an intensive CCC workshop with Nebeker, and he was right. She still paints, but now she focuses on printmaking.

Many of Souza’s works are landscapes. “Our identities are influenced by the spaces we visit,” she says. “Places linger in our memories and create powerful impressions on us. They contribute to our characters and the communities we participate in. We share this diverse planet with each other and carry its special landscapes within us.”

Despite her emphasis on landscape, Souza is “interested more in light and color than objects.” Indeed, it may be her use of color that most reveals her Hawaiian roots. She creates monoprints, which are the most painterly printmaking technique, almost printed paintings, using successive layers to build light and shadow. Souza calls monoprints, “the perfect medium for building environments and space.”

Now, Souza is “focusing on the business side of art,” and she belies the common perception of artists as poor businesspersons. Not only is she working on the Portland commission, she now has an agreement to supply art for Hilton hotels.

The question is not whether Miki’ala Souza can succeed as an artist, but where her success will take her.