Still a fishing town

Published 3:03 am Thursday, April 28, 2011

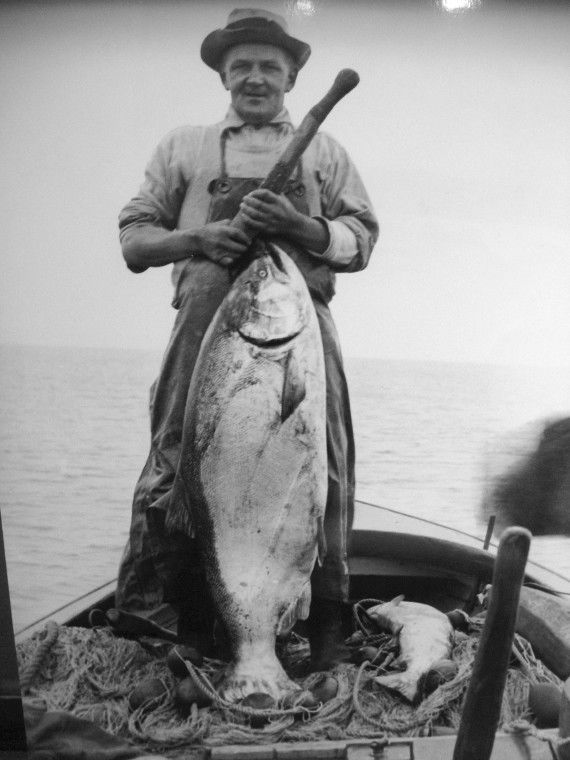

- Salmon could reach huge sizes in the early days of Astoria's fishing industry. Photo Clatsop County Historical Society.

Back in the late 1960s and ’70s, I spent considerable time in Astoria. I had relatives there and they were all fishermen. I became enamored with gillnetting, to the point that I made a movie about it. Many cool nights and days were spent out on the Columbia, bobbing up and down in a gillnetter to get the scenes needed. At the time, I didn’t know I was witnessing the twilight of the heyday of a fishing tradition, one that had sustained Astoria and its intrepid fishers for many decades.

The glory days of king salmon are now resigned to pictures on museum walls and in names such as Cannery Pier Hotel and Silver Salmon Restaurant. The industry is not gone by any measure, and still remains an important part of Astoria’s economy, but in its wake a new Astoria has emerged under the shadow of those glory days. Rather than salmon by the tonnage being offloaded from hordes of gillnet boats, tourists now hit the docks from cruise ships en masse. In the remade Astoria, another king has emerged: the tourist.

Gone are the numerous canneries that lined the docks, gone are the many net racks draped with gillnets, and gone is the plethora of iconic gillnet boats that bobbed by the piers. All of that may be gone in its plentitude, but not forgotten, because the riches of the sea helped make this town, and imbued it with a special quality that still holds its grip on it today. Astoria, at its heart, is still a fishing town.

Long before written history recorded its importance to the area, long before Astoria became a reality, fruit from the sea had sustained inhabitants living at the confluence of the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean: Salmon, crab, clams and sturgeon were among the importance sources of food for many tribes, as well as vital to their culture, economy and spirituality. So plentiful were salmon, pre-1800s estimates of annual runs of salmon and steelhead were believed to have reached 10 million to 12 million fish.

By first contact with Europeans in the late 1700s, Columbia River native inhabitants were expert at gathering, using traps and nets to catch seafood, particularly salmon.

Robert Stuart, who arrived on the ship Tonquin in 1811, noted in his journal that salmon purchased from the Chinook were “by far the finest fish I ever beheld.” Fish were destined to become an important food source for all the early explorers and pioneers in the area as well.

Once the Europeans had established a foothold in the area, the Hudson’s Bay Company began packing salmon for export in 1823. It was the death knell for native inhabitants. A mere 32 years later, treaties forced the Columbia River tribes to cede most of their lands.

It’s thought that the salmon canning industry got its start in Astoria. The 1880 U.S. Census indicates fishers made up almost one-fifth of the population, mostly of Scandinavian descent, and the Chinese working the canneries made up another one-third. No doubt about it, salmon was king. In those days, a fresh salmon could even get you into a girlie show on the docks in lieu of cash. It was a rough and rowdy town then. The Oregonian depicted Astoria during fishing season as “the most wicked place on earth for its population.” The Astoria Daily Budget echoed with the condemnation, “Fishermen spent most of their time and all their money in those festering man-traps where they barter their good fish for the vilest kind of rot-gut.” Harsh words, but the work was dangerous and fit for only the toughest of men. The boats were often rowed or under sail, and no power equipment assisted the haul-in of that precious load of silvery gold.

Late in the century, salmon canneries had become Astoria’s major industry, lagging only behind wheat and flour as the leading export in Oregon. By this time, 55 canneries were in operation at or near the mouth of the Columbia River.

But from 1890 forward, for the next 30 years, the Oregon fishery would decline because of overfishing, irrigation upstream, tributary dams and pollution. Still, by 1935, Oregon fisheries were yielding more than $242 million, 75 percent from salmon.

For decades, salmon canneries ruled, but with the steady decline of the salmon runs, the reduction in commercial fishing in the lower Columbia and the predictable shift of salmon fishing to Alaska, the Astoria canneries, one by one, closed. The doors shut on the last, Bumble Bee Seafoods, in 1980. An era had ended.

The decline of the salmon runs and salmon fishing hit Astoria hard. Salmon fishing was not only the city’s major economic activity, it was also a way of life that had shaped the town. In 1996, Jim Bergeron, then the Oregon State University extension agent for commercial fishing, remarked, “My job is like crisis counseling.”

Of course, salmon wasn’t the only seafood industry in Astoria. There is evidence crabbing on the Pacific Coast was under way, in some form, by the late 1800s. By the mid-1930s, a nascent crab industry began to develop in the area, adding more variety to the seafood economy. Today, according to Hugh Link, assistant administrator of the Oregon Dungeness Crab Industry, “There have been years that Astoria/Warrenton has been the number one port on the coast. They are typically in the top three.”

Even though Columbia River salmon rebounded in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the industry is but a shadow of its historic size. While fishing and fishing-related business is still important to Astoria’s economy, something new was needed. The city found it in tourism, but the transition required some new thinking, as Skip Hauke, executive director of the Astoria-Warrenton Area Chamber of Commerce, will tell you: “It was a change in attitude brought about by our council and mayor. If anybody had said 20, even 10 years ago, that Astoria would be a major port for cruise ships, they would have been laughed at, but by pushing forward and thinking outside the box, we’re now one of their favorite stops. I read an article in one of the cruise ship magazines it was a comment from the captain of the Radiance of the Sea he was asked how Astoria stacked up as a port of call. He said, On a scale of one to 10, Astoria is a 12,’ and a lot of that can be credited to our volunteers and businesses.”

Hauke also thought the Riverwalk played its part. “Once we got that in place, that five-mile stretch along our beautiful river, it kind of got things going. It changed the direction but yet kept the character of the city. We wanted to have a working waterfront that people can visit and walk along. We didn’t strip away all the fish processing and old buildings; a lot of them are still there it’s still a working waterfront. It would have been easy to strip it all away and put up condos, but I think the visitors we have here appreciate that. You can take a trolley ride and still get the feeling of old Astoria.”

Hauke was adamant to make the point that tourism didn’t replace the fishing industry here; it complemented it. “We’re thankful for tourism, but it doesn’t bring in the living wages that fishing does we couldn’t do it on tourism alone. The fishing industry is still vital. We bring in a lot of tuna here, crab, our trawl fleet fishing for all kinds of bottom fish is still very productive, and of course we still have salmon gillnetting in the river. We don’t have canneries any more except custom canning, but we still have several fish processing plants. The spinoff from that industry is quite large as well … without the fishing industry, we wouldn’t have Englund Marine and Industrial Supply, which is a huge company on the entire coast. They started out serving the commercial industry but they have made a transition to sport fishing and other areas. Next door there is a small boat repair yard, beside that a haulout facility. Fishing is still huge.”

Tourism, however, brought a much-needed steadiness to the year-round economy of the town, as Hauke points out. “I think it has balanced our town. The tourist season used to be just during the summer months, but now it’s stretched out from April to October. We have 19 cruise ships coming out this year. It’s been a huge transformation. We have become a destination. Two weeks ago, we had a story in the New York Daily News, three days later in the New York Times. It’s very powerful to get that kind of press.”

With its new and refurbished hotels, friendly shops and plentiful restaurants, Astoria indeed has a new face, but it owes a great debt to the fishers and the fish that built this town. It is now a city of two kings.